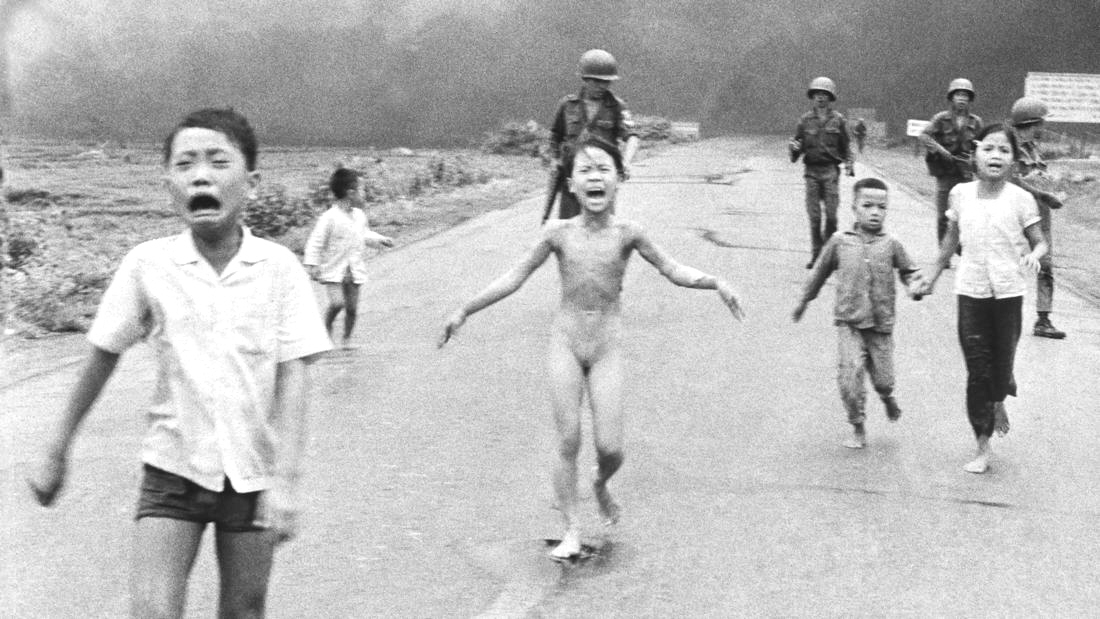

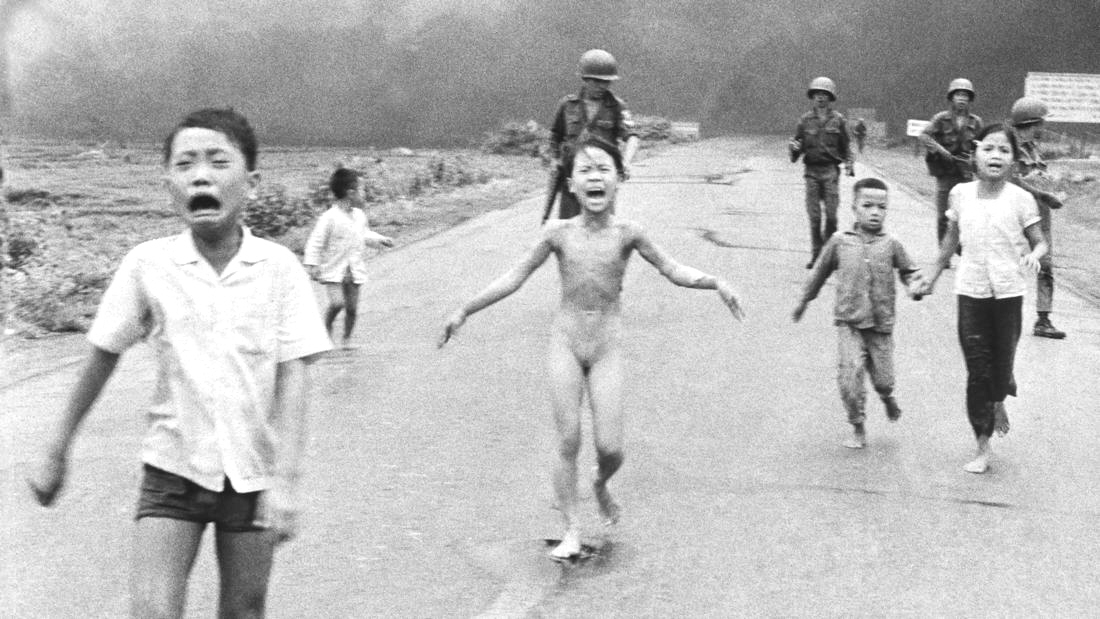

Photo caption: Kim

Phuc, center, runs from a napalm strike near Trang Banb, Vietnam, on June 8, 1972, in this

Pulitzer Prize-winning photo. Phuc suffered serious burns over a third of her body. (Nick

Ut / Associated Press)

Photo caption: Kim

Phuc, center, runs from a napalm strike near Trang Banb, Vietnam, on June 8, 1972, in this

Pulitzer Prize-winning photo. Phuc suffered serious burns over a third of her body. (Nick

Ut / Associated Press)New U.N. chief calls for ‘whole new approach’ to prevent war

New U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres on January 10 called for a “whole new approach” to prevent war, in his first address to the Security Council since taking office. Guterres took over from Ban Ki-moon on Jan. 1 with a promise to shake up the world body and boost efforts to tackle global crises, from the carnage in Syria to the bloodshed in South Sudan.

The former Portuguese prime minister and head of the U.N. refugee agency told a council debate on conflict prevention that too much time and resources were being spent on responding to crises rather than preventing them. “People are paying too high a price,” he said. “We need a whole new approach.”

The U.N. chief announced plans to launch an initiative to enhance mediation as part of his commitment to a “surge in diplomacy for peace,” but there were no details.

Guterres is expected to have a more hands-on approach than his predecessor Ban who left most of the mediation efforts to his special envoys.

The new U.N. chief is confronted with a deeply divided Security Council that has been unable to take decisive action to end the war in Syria, now in its sixth year. “Too many prevention opportunities have been lost because member states mistrusted each other’s motives, and because of concerns over national sovereignty,” said Guterres, in a veiled swipe at council powers.

“Today, we need to demonstrate leadership and strengthen the credibility and authority of the United Nations by putting peace first,” he said.

Complicating Guterres’ plan to revitalize U.N. diplomacy is the question mark hanging over the foreign policy of the new U.S. administration under President Donald Trump.

– Agence-France Presse,

January 10, 2017

PeaceMeal, Jan/February 2017

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)

Post-September 11 wars have cost $4.79 trillion

Paul D. Shinkman

On September 14, 2001, President George W. Bush visited the still-smoldering ruins of the World Trade Center and addressed first responders working to clear debris and find victims of the attack. When one person shouted that he couldn’t hear the president, Bush famously responded that “the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon!”

Fifteen years later, after protracted conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan and now Syria, as well as operations in Pakistan, Libya, Yemen and Somalia, Boston University analyst Neta Crawford with the Cost of War project has calculated the price of that promise.

According to a study released September 9 through Brown University’s Watson Institute of International and Public Affairs, government spending on the military, diplomacy, foreign aid, homeland security and services to veterans have cost U.S. taxpayers upward of $4.79 trillion in the post-September 11 era.

The accounting is much broader in its scope than typical war spending calculations, which generally focus on tallying the cost of bullets or battleships. It instead yields an imprecise figure in an attempt to find a truer dollar amount, despite even Congressional Budget Office declarations that “it is impossible to determine precisely how much has been spent” on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The study captures the immensity of America’s commitments to defeating terrorism at home and abroad and the continuing financial toll that takes. It estimates that the cumulative interest the U.S. will have to pay for its wars will balloon to $7.9 trillion by 2053 if it does not change the way it pays for its wars.

The study also observes that current spending levels are conservative and don’t account for the fact that President Barack Obama, for example, has failed to follow through on his pledges to further reduce the number of troops in war zones like Afghanistan.

Instead, the U.S. has held steady in Afghanistan and has increased its presence in Iraq as that country’s shaky military prepares to take on the Islamic State group in the city of Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest. A spokesman for the U.S.-led coalition in Baghdad said that as of September 8 4,460 declared U.S. forces are in Iraq, up from 4,000 the week before. The current cap Obama has placed on that campaign is 4,640, though commanders there are considering whether that should be raised. The numbers do not include the Pentagon’s undeclared, or temporary, troops also contributing to the war.

“No set of numbers can convey the human toll of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, or how they have spilled into the neighboring states of Syria and Pakistan, and come home to the U.S. and its allies in the form of wounded veterans and contractors,” Crawford wrote. “Yet, the expenditures noted on government ledgers are necessary to apprehend, even as they are so large as to be almost incomprehensible.”

The tally of $4.79 trillion comes from Pentagon and State Department spending for its emergency war budget, known formally as the Overseas Contingency Operations or OCO budget of $1.74 trillion since 2001. That budget itself has come under harsh criticism for becoming a slush fund for Congress to pay for other military-related spending as it grapples with the across- the-board budget cuts known as sequestration. Other defense, homeland security and veterans affairs spending brings that total up to $3.69 trillion, with an additional $1.1 trillion in projected funding for the coming fiscal year.

Most of these OCO funds have gone to Iraq and Afghanistan, with $805 billion and $783 billion in spending, respectively and the rest dedicated to operations in Syria, Pakistan, joint counterterrorism operations with Canada known as Operation Noble Eagle and other miscellaneous missions.

Crawford’s totals offer a sobering assessment as to how the U.S. should prepare when its leaders pledge swift, glorious wars performed on limited budgets. As she points out, “current and future costs of war greatly exceed prewar and early estimates. Optimistic assumptions and a tendency to underestimate and undercount war costs have, from the beginning, been characteristic of the estimates of the budget costs and the fiscal consequences of these wars,” she writes.

But the wars press on, questioning whether voters will have a chance to truly reflect on the decision to engage in conflict abroad as they consider two leading presidential candidates who have expressed their own interest in further overseas adventures.

– U.S. News & World

Report, September 9, 2016

PeaceMeal, Sept/October 2016

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)

World lost more than $13 trillion last year because of war

Violence and worsening conflict cost the world more than $13.6 trillion last year, according to an annual study of the toll of violence worldwide. That figure amounts to some 13 percent of global Gross Domestic Product.

The analysis can be found within the Global Peace Index 2016 report, which is put out each year by the Institute of Economics and Peace, an Australia-based think-tank. It ranked 163 countries on the degree of peace within their borders. The results since the initiative began are not encouraging: “The last decade has seen a historic decline in world peace, interrupting the long term improvements since WWII,” a press release indicates.

Moreover, peace and safety, like the incomes of the rich and poor, are growing more unequal, with prosperous, relatively harmonious countries improving, according to the index, and countries already wracked by conflict and violence getting worse.

The five most precipitous declines don’t even include Syria, which is in the grips of a brutal five-year civil war that has killed more than 250,000 people and triggered an unprecedented regional refugee and security crisis.

“The historic 10-year deterioration in peace has largely been driven by the intensifying conflicts in the [Middle East and North Africa],” says the report. “Terrorism is also at an all-time high, battle deaths from conflict are at a 25-year high, and the number of refugees and displaced people are at a level not seen in 60 years.”

The impact of terrorism deteriorated in 77 countries, while improving in 48. Only 37 of the 163 countries measured had no impact of terrorism. The largest deterioration in this indicator was in the Middle East and North Africa.

The estimated cost of conflict to the world’s resources in 2015 is a tabulation based on military spending, the damage caused by conflict, and losses from crime and interpersonal violence. The report stresses how disproportionately greater such security spending is compared to global efforts to build and preserve peace.

– edited from The

Washington Post, June 9, 2016

PeaceMeal, July/August 2016

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)

Vatican conference urges abandonment of ‘just war’ theory

A monumental, first-of-its-kind conference was held April 11-13 in Rome with the purpose of examining the Catholic Church’s traditional “just war” theory and more fully developing a vision of nonviolence consistent with Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount.

The Nonviolence and Just Peace Conference, co-sponsored by the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace and the Catholic peace fellowship Pax Christi International, gathered together an international group of approximately 80 bishops, theologians, priests, sisters and laypersons — all experienced nonviolent social justice and peace leaders — to begin to formulate for the church a Gospel-based, active, nonviolent strategy to counter violence, armed conflict and war.

Jesus taught the first leaders of his church to respond to violence with total nonviolence, which produces the only real and lasting peace, unlike the false “peace” of the world which violently conquers enemies. But after three centuries of Christians striving to follow that nonviolent teaching, often suffering persecution and death, the Christian faith was made the official religion of the Roman Empire. Christians then began fighting wars for the empire. And, sadly, Christians have been fighting wars for empires ever since.

For centuries, the Catholic Church made the just war theory its standard teaching on war. In recent decades, however, church leadership has realized that the just war theory is inadequate and outmoded. Its focus is war, not peace.

The just war theory was derived from the pagan philosopher Cicero by way of the fourth-century theologian Augustine of Hippo. It considers a war morally justified if it is fought for a just cause as a last resort by a legitimate authority acting with good intentions. The war must have a reasonable chance of success and of being “proportional,” that is, doing more good than harm. It also must be conducted by moral means, avoiding, for example, deliberate attacks on civilians.

But what it sets out to do — discriminate justified from unjustified wars — has been rendered null and void by the massive, indiscriminate violence of modern wars. The key criteria of the theory are never met today.

Civilian deaths in World War I were 10 percent of the deaths. But in modern wars, such as the internal conflict in Syria or the U.S. invasion of Iraq, civilian deaths now range from 80 percent to 90 percent of all war casualties. By the very criteria of the theory, in our era there is no such thing as a “just” war.

Conference participants urged that the just war theory be replaced with a Just Peace strategy. One of the attendees, Marie Dennis, co-president of Pax Christi International, said that most of the participants came from countries where war and violent conflict have been the reality for too many years. Dennis said their message over and over again was: “We are tired of war.”

A sparkling sign of the times that supports and illuminates the teaching of the Sermon on the Mount is the recent track record of nonviolent action campaigns. Given the last 60 years of experimentation with nonviolence — as Gandhi predicted — people of faith are beginning to see that as violence continues its wasteful, ineffective way, there is indeed an alternative worth embracing. We have witnessed the achievements, against all odds, of nonviolent campaigns across the globe — in Poland, East Germany, South Africa, the Philippines, Serbia, Tunisia and our own civil rights struggle.

Increasingly, research is validating the superiority of nonviolence over violence in terms of effectiveness. Erica Chenoweth, a professor at the University of Colorado, demonstrates that nonviolent resistance campaigns over the last 50 years have been twice as effective as violent campaigns in achieving their intended results. In addition, the regimes that have been established through nonviolent means are much more likely to remain at peace after their struggles.

The Nonviolence and Just Peace Conference produced a guiding document titled “An Appeal to the Catholic Church to Re-Commit to the Centrality of Gospel Nonviolence.” At the end of this document there is a call for the church to:

• no longer use or teach the “just war” theory;

• integrate Gospel nonviolence into the life and work of the church through dioceses, parishes, schools and seminaries;

• promote strategies of nonviolent resistance, restorative justice and unarmed civilian protection; and

• continue advocating for the abolition of war and nuclear weapons.

– edited from the

National Catholic Reporter, April 9 & 25, 2016

PeaceMeal, May/June 2016

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)

Napalmed in Vietnam, ‘girl’ heals scars in United States

MIAMI – In the photograph that made Kim Phuc a living symbol of the Vietnam War, her burns aren’t visible — only her agony as she runs wailing toward the camera, her arms flung away from her body, naked because she has ripped off her burning clothes. More than 40 years later, she can hide the scars beneath long sleeves, but a single tear down her otherwise radiant face betrays the pain she has endured since that errant napalm strike in 1972.

Photo caption: Kim

Phuc, center, runs from a napalm strike near Trang Banb, Vietnam, on June 8, 1972, in this

Pulitzer Prize-winning photo. Phuc suffered serious burns over a third of her body. (Nick

Ut / Associated Press)

Photo caption: Kim

Phuc, center, runs from a napalm strike near Trang Banb, Vietnam, on June 8, 1972, in this

Pulitzer Prize-winning photo. Phuc suffered serious burns over a third of her body. (Nick

Ut / Associated Press)

Now she has a new chance to heal — a prospect she once thought possible only in a life after death. “So many years I thought that I have no more scars, no more pain when I’m in heaven. But now — heaven on Earth for me!” Phuc, 52, said upon her arrival in Miami to see a dermatologist who specializes in laser treatments for burn patients. In September, she began a series of laser treatments that her doctor, Jill Waibel of the Miami Dermatology and Laser Institute, says will smooth and soften the pale, thick scar tissue that ripples from her left hand up her arm, up her neck to her hairline and down almost all of her back.

Photo caption: Dr.

Jill Waibel of Miami examines kim Phuc, now 52, before the first of several laser

tretments. (Nick Ut / Associated Press)

Photo caption: Dr.

Jill Waibel of Miami examines kim Phuc, now 52, before the first of several laser

tretments. (Nick Ut / Associated Press)

Even more important to Phuc, Waibel says, the treatments also will relieve the deep aches and pains that plague her to this day.

With Phuc are her husband, Bui Huy Toan, and another man who has been part of her life since she was 9, Los Angeles-based Associated Press photojournalist Nick Ut.

“He’s the beginning and the end,” Phuc says of the man she calls “Uncle Ut.” “He took my picture and now he’ll be here with me with this new journey, new chapter.”

It was Ut, now 65, who captured Phuc’s agony on June 8, 1972, after the South Vietnamese military accidentally dropped napalm on civilians in Phuc’s village outside Saigon.

Ut remembers the girl screaming in Vietnamese, “Too hot! Too hot!” He put her in the AP van where she crouched on the floor, her burned skin raw and peeling off her body as she sobbed and said, “I think I’m dying, too hot, too hot. I’m dying.”

Phuc suffered serious burns over a third of her body. At that time, most people who sustained such injuries over 10 percent of their bodies died. Ut took her to a hospital. Only then did he return to the AP’s bureau in Saigon to file his photographs, including the one of Phuc on fire that would win the Pulitzer Prize.

Napalm sticks like a jelly, so there was no way for victims like Phuc to outrun the heat, as they could in a regular fire. “The fire was stuck on her for a very long time,” Waibel says, and destroyed her skin down through the layer of collagen, leaving her with scars almost four times as thick as normal skin.

Although she spent years doing painful exercises to preserve her range of motion, her left arm still doesn’t extend as far as her right arm, and her desire to learn how to play the piano has been thwarted by stiffness in her left hand. Triggered by scarred nerve endings that misfire at random, her pain is especially acute when the seasons change in Canada, where Phuc defected with her husband in the early 1990s. The couple live outside Toronto, and they have two sons, ages 21 and 18.

Phuc says her Christian faith brought her physical and emotional peace “in the midst of hatred, bitterness, pain, loss, hopelessness” when the pain seemed insurmountable. “No operation, no medication, no doctor can help to heal my heart. The only one is a miracle, [that] God loves me,” she says. “I just wish one day I am free from pain.”

Ut thinks of Phuc as a daughter, and he worried when, during their regular phone calls, she described her pain. When he travels now in Vietnam, he sees how the war lingers in hospitals there, in children born with defects attributed to Agent Orange and in others like Phuc, who were caught in napalm strikes. If their pain continues, he wonders, how much hope is there for Phuc?

He also is worried about the treatments. “Forty-three years later, how is laser doing this? I hope the doctor can help her.... now she’s over 50! That’s a long time.”

Waibel has been using lasers to treat burn scars, including napalm scars, for about a decade. She expects Phuc to need as many as seven treatments over the next eight or nine months. Each treatment typically costs $1,500 to $2,000, but Waibel offered to donate her services when Phuc contacted her for a consultation.

At the first treatment, a scented candle lends a comforting air to the procedure room, and Phuc’s husband holds her hand in prayer. Once sedatives have been administered and numbing cream spread thickly over Phuc’s skin, Waibel dons safety glasses and aims the laser, which heats skin to the boiling point to vaporize scar tissue. The procedure creates microscopic holes in the skin, which allows topical, collagen-building medicines to be absorbed deep through the layers of tissue.

Wrapped in blankets, drowsy from painkillers, her scarred skin a little red from the procedure, Phuc made a little fist pump. Compared with the other surgeries and skin grafts when she was younger, “This was so light, just so easy,” she says.

A couple of weeks later, home in Canada, Phuc says her scars have reddened and feel tight and itchy as they heal, but she’s eager to continue the treatments. “Maybe it takes a year,” she says. “But I am really excited — and thankful.”

– edited from The

Associated Press, October 27, 2015

PeaceMeal, Nov/December 2015

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)

From Vietnam to Iraq: Turning a nightmare into a fairy tale

A few years ago we had reason to hope that our seemingly endless wars — this time in distant Iraq and Afghanistan — were finally over or soon would be. In December 2011, in front of U.S. troops at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, President Obama proclaimed an end to the American war in Iraq. “We’re leaving behind a sovereign, stable, and self-reliant Iraq,” he said proudly. “This is an extraordinary achievement.” In a similar fashion, last December the president announced that in Afghanistan “the longest war in American history is coming to a responsible conclusion.”

If only. Instead, warfare, strife, and suffering of every kind continue in both countries, while spreading across ever more of the Greater Middle East. American troops are still dying in Afghanistan and in Iraq the U.S. military is back, once again bombing and advising, this time against the Islamic State (or Daesh), an extremist spin-off from its predecessor al-Qaeda in Iraq, an organization that only came to life well after (and in reaction to) the U.S. invasion and occupation of that country. It now seems likely that the nightmare of war in Iraq and Afghanistan, which began decades ago, will simply drag on with no end in sight.

The Vietnam War, long as it was, did finally come to a decisive conclusion. When Vietnam screamed back into the headlines in early 1975, 14 North Vietnamese divisions were racing toward Saigon, virtually unopposed. Tens of thousands of South Vietnamese troops (shades of the Iraqi army in 2014) were stripping off their military uniforms, abandoning their American equipment, and fleeing. With the massive U.S. military presence gone, what had once been a brutal stalemate was now a rout, stunning evidence that “nation-building” by the U.S. military in South Vietnam had utterly failed, as it would in the twenty-first century in Iraq and Afghanistan. ... The blood-soaked American effort to construct a permanent non-Communist nation called South Vietnam ended in humiliating defeat.

It’s hard now to imagine such a climactic conclusion in Iraq and Afghanistan. Unlike Vietnam, where the Communists successfully tapped a deep vein of nationalist and revolutionary fervor throughout the country, in neither Iraq nor Afghanistan has any faction, party or government had such success or the kind of appeal that might lead it to gain full and uncontested control of the country. Yet in Iraq, there have at least been a series of mass evacuations and displacements reminiscent of the final days in Vietnam. In fact, the region, including Syria, is now engulfed in a refugee crisis of staggering proportions with millions seeking sanctuary across national boundaries and millions more homeless and displaced internally.

Last August, U.S. forces returned to Iraq (as in Vietnam four decades earlier) on the basis of a “humanitarian” mission. Some 40,000 Iraqis of the Yazidi sect, threatened with slaughter, had been stranded on Mount Sinjar in northern Iraq surrounded by Islamic State militants. While most of the Yazidi were, in fact, successfully evacuated by Kurdish fighters via ground trails, small groups were flown out on helicopters by the Iraqi military with U.S. help. When one of those choppers went down wounding many of its passengers but killing only the pilot, General Majid Ahmed Saadi, New York Times reporter Alissa Rubin, injured in the crash, praised his heroism. Before his death, he had told her that the evacuation missions were “the most important thing he had done in his life, the most significant thing he had done in his 35 years of flying.”

In this way, a tortured history inconceivable without the American invasion of 2003 and almost a decade of excesses, including the torture and abuse at Abu Ghraib, as well as counterinsurgency warfare, finally produced a heroic tale of American humanitarian intervention to rescue victims of murderous extremists. The model for that kind of story had been well established [in Vietnam] in 1975. ...

The time may come, if it hasn’t already, when many of us will forget, Vietnam-style, that our leaders sent us to war in Iraq falsely claiming that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction he intended to use against us; that he had a “sinister nexus” with the al-Qaeda terrorists who attacked on 9/11; that the war would essentially pay for itself; that it would be over in “weeks rather than months”; that the Iraqis would greet us as liberators; or that we would build an Iraqi democracy that would be a model for the entire region. And will we also forget that in the process nearly 4,500 Americans were killed along with perhaps 500,000 Iraqis, that millions of Iraqis were displaced from their homes into internal exile or forced from the country itself, and that by almost every measure civil society has failed to return to pre-war levels of stability and security?

The picture is no less grim in Afghanistan.

What silver linings can possibly emerge from our endless wars? If history is any guide, I’m sure we’ll think of something.

Christian Appy is a professor of history at the University of Massachusetts and author of three books about the Vietnam War, including the just-published American Reckoning: The Vietnam War and Our National Identity. This is an excerpt from a longer article posted on Truthdig.com, April 27, 2015, reprinted in PeaceMeal, May/June 2015.

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)

A recent article on whether America’s all-volunteer military is desensitizing us to war might be right for some. I don’t really dispute most of it.

In my case, I am still dealing with the traumas created by service in Vietnam. I’m a Marine veteran who served in that long-forgotten war from 1968-69.

I don’t think it will ever leave me, but I am learning to make an uneasy peace with it. I have friends who served in both Gulf wars as well as Afghanistan. I can only imagine their daily horrors as I must deal with mine.

GORDON BOONE

Richland

The above letter was published in the Tri-City Herald on January 24, 2013, and in PeaceMeal, Jan/February 2013

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)

Boy Scouts of America “Handbook for Boys,” 1929

War is one of the tragedies of the life of the world. In its wake stalk sorrow, poverty, disease, moral letdown, debt, hatreds, fears.

One-third of the taxation of the world is either to pay for old wars or prepare for new.

War tears down civilization. The effort of home, church, school and state is for us to guard life and respect property—war says kill and destroy. Tragic as is the wastage of billions in property and millions of lives—this reversal of the channels of civilized order is serious in its influence upon youth.

The insane thing about war is that, after killing and destroying, THEN folks must gather around a table—find what the points at issue are and adjust them finally. In a sane world this world be done FIRST. It is not CONFLICT but CONFERENCE that settles— therefore have it first. ...

The Civil War cost us 1,000,000 men and $2,750,000,000 of indebtedness, to say nothing of the property damage. It set back the north 10 years, the south by 50!

The World War left even greater ruin in its wake. It cost the world 20,000,000 in dead and maimed and cost not less than $500,000,000,000—and all avoidable.

The Boy Scout Movement around the world is creating world friendships, making community of interest among nations clear, and should help prevent future wars.

What individuals and cities and states have learned fairly well—namely to settle their differences before impartial judges, may yet be realized between nations.

Why not? And the Scout who LIVES good will and fairness and peace is helping the world recover from the disease of WAR.

– PeaceMeal, Sept/October 2012

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)

The pictures of

war you aren’t supposed to see

The pictures of

war you aren’t supposed to see

Chris Hedges

Photo caption: An Iraqi mother takes her dead son into her arms. The 6-year-old was killed on the way home from enrolling for his first year of school. Associated Press photo by Adem Hadei.

War is brutal and impersonal. It mocks the fantasy of individual heroism and the absurdity of utopian goals like democracy. In an instant, industrial warfare can kill dozens, even hundreds, of people who never see their attackers. The power of these industrial weapons is indiscriminate and staggering. They can take down apartment blocks in seconds, burying and crushing everyone inside. They can demolish villages and send tanks, planes and ships up in fiery blasts. For those who survive, the wounds result in terrible burns, blindness, amputation and lifelong pain and trauma. No one returns the same from such warfare.

In Peter van Agtmael’s “2nd Tour, Hope I Don’t Die” and Lori Grinker’s “Afterwar: Veterans From a World in Conflict,” we see pictures of war that are almost always hidden from public view. These pictures are shadows, for only those who go to and suffer from war can fully confront the visceral horror of it, but they are at least an attempt to unmask war’s savagery.

“Over ninety percent of this soldier’s body was burned when a roadside bomb hit his vehicle, igniting the fuel tank and burning two other soldiers to death,” reads the caption in Agtmael’s book next to a photograph of the bloodied body of a soldier in an operating room. “His camouflage uniform dangled over the bed, ripped open by the medics who had treated him on the helicopter. Clumps of his skin had peeled away, and what was left of it was translucent. He was in and out of consciousness, his eyes stabbing open for a few seconds. As he was lifted from the stretcher to the ER bed, he screamed ‘Daddy, Daddy, Daddy, Daddy,’ then ‘Put me to sleep, please put me to sleep.’ There was another photographer in the ER, and he leaned his camera over the heads of the medical staff to get an overhead shot. The soldier yelled, ‘Get that f---ing camera out of my face.’ Those were his last words.”

Most film and still images of war are shorn of the heart-pounding fear, awful stench, deafening noise and exhaustion of the battlefield. Such images turn chaos into an artful war narrative. They turn war into porn. The reality of war violence is different — senseless and useless. It leaves behind nothing but death, grief and destruction.

War’s effects are what the state and the press work hard to keep hidden. If we really saw what war does to young minds and bodies, it would be harder to embrace the myth of war. If we had to stand over the mangled corpses of the eight schoolchildren killed in Afghanistan the last week of December and listen to the wails of their parents, we would not be able to repeat clichés about liberating the women of Afghanistan or bringing freedom to the Afghan people. This is why war is carefully sanitized. The mythic visions of war keep it heroic and entertaining. And the press is as guilty as Hollywood.

The wounded, the crippled and the dead are, in this great charade, swiftly carted off stage. They are war’s refuse. We do not see them. We do not hear them. The message they tell is too painful for us to hear. We prefer to celebrate ourselves and our nation by imbibing the myth of glory, honor, patriotism and heroism. The public manifesta-tions of gratitude are reserved for veterans who dutifully read from the script handed to them by the state. The veterans trotted out for viewing are those who are compliant and palatable, those we can stand to look at without horror, those who are willing to go along with the lie that war is about patriotism and is the highest good. “Thank you for your service,” we are supposed to say.

Gary Zuspann, who lives in a special enclosed environment in his parent’s home in Waco, Texas, suffering from Gulf War syndrome, speaks in Grinker’s book of feeling like “a prisoner of war” even after the war had ended. “Basically they put me on the curb and said, okay, fend for yourself,” he says in the book. “I was living in a fantasy world where I thought our government cared about us and they take care of their own. I believed it was in my contract, that if you’re maimed or wounded during your service in war, you should be taken care of. Now I’m angry.”

Despair and suicide grip survivors. More Vietnam veterans committed suicide after the war than the 58,236 who were killed during it. The inhuman qualities drilled into soldiers and Marines in wartime defeat them in peacetime. On the professional killers long journey to recovery, many never readjust. They cannot connect again with wives, children, parents or friends, retreating into personal hells of self-destructive anguish and rage.

“They program you to have no emotion — like if somebody sitting next to you gets killed, you just have to carry on doing your job and shut up,” Steve Annabell, a British veteran of the Falklands War, says to Grinker. “When you leave the service, when you come back from a situation like that, there’s no button they can press to switch your emotions back on. So you walk around like a zombie.”

“To get you to join up, they do all these advertisements ... but they don’t show you getting shot at and people with their legs blown off or burning to death,” he says. “It’s just bullshit. And they never prepare you for it. They can give you all the training in the world, but it’s never the same as the real thing.”

Look beyond the nationalist cant used to justify war. Look beyond Barack Obama’s ridiculous rhetoric about finishing the job or fighting terror. Focus on the evil of war. War begins by calling for the annihilation of the others but ends ultimately in self-annihilation. It corrupts souls and mutilates bodies. It destroys homes and villages and murders children on their way to school. War is a scourge. It is a plague. It is industrial murder. And before you support war, especially the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, look into the hollow eyes of the men, women and children who know it.

Chris Hedges is a Pulitzer Prize-winning correspondent who covered conflicts for two decades in Central America, Africa, the Middle East and the Balkans. The author or co-author of a dozen books, he writes a column published every Monday on Truthdig.com. This article, edited here, was posted on January 4, 2010.

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)

Bosnian Serb gets 30 years for genocide

SARAJEVO - Bosnia’s war crimes court jailed a former Serb officer for 30 years October 16 on a charge of genocide for killing dozens of people during the 1995 Srebrenica massacre of Muslims. Former army captain Milorad Trbic, 51, was found guilty of taking part in the persecution of Bosnian Muslims from the Srebrenica enclave and their detention, summary executions, burial and covering traces of the crime.

Some 8,000 Muslim men and boys were killed in the Srebrenica massacre after Bosnian Serb forces captured the enclave on July 11, 1995, in what is regarded as Europe’s worst atrocity since World War II.

Trbic took part in a “joint criminal enterprise” with other Serb army officers and organized the forcible transfer of Muslims from Srebrenica between July 10 and November 30, 1995, the head of the judicial council Davorin Jukic said. Trbic supervised the detention of thousands of Muslims in several schools around Srebrenica, where they were kept in inhuman conditions, as well as transportation to the killing fields where they were executed en masse, Jukic said.

Trbic himself shot dead a group of “at least 20 Muslims” in the Grbavci school on one occasion, and a group of “at least 5 Muslims” in the Rocevici school on another occasion. He was also involved in the exhumation of victims from original mass graves and their later transfer to “secondary mass graves” to hide traces of the crime.

Remains of more than 6,000 Srebrenica victims have been found in mass graves across eastern Bosnia but only about 3,800 bodies have been identified so far.

After the 1992-95 Bosnian war, Trbic escaped to the United States but was found guilty of breaking immigration laws. In 2005 he was handed over to the Hague-based International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, which transferred him to Bosnia for trial in June 2007.

The court acquitted Trbic of three other counts of genocide due to lack of evidence, in a decision that angered relatives of the victims.

– edited from Reuters,

16 October 2009

PeaceMeal, Nov/December 2009

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)

Chris Hedges

Pulitzer prize–winner Chris Hedges spent nearly two decades as a war correspondent for The New York Times and other newspapers. He is the author of the bestselling “War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning” and the newly released “Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle.”

The crisis faced by combat veterans returning from war is not simply a profound struggle with trauma and alienation. It is often, for those who can slice through the suffering to self-awareness, an existential crisis. War exposes the lies we tell ourselves about ourselves. It rips open the hypocrisy of our religions and secular institutions. Those who return from war have learned something which is often incomprehensible to those who have stayed home. We are not a virtuous nation. God and fate have not blessed us above others. Victory is not assured. War is neither glorious nor noble. And we carry within us the capacity for evil we ascribe to those we fight.

Those who return to speak this truth, such as members of Iraq Veterans Against the War, are our contemporary prophets. But like all prophets, they are condemned and ignored for their courage. They struggle, in a culture awash in lies, to tell what few have the fortitude to digest. They know that what we are taught in school, in worship, by the press, through the entertainment industry and at home, that the melding of the state’s rhetoric with the rhetoric of religion, is empty and false.

The words these prophets speak are painful. We, as a nation, prefer to listen to those who speak from the patriotic script. We prefer to hear ourselves exalted. If veterans speak of terrible wounds visible and invisible, of lies told to make them kill, of evil committed in our name, we fill our ears with wax. Not our boys, we say, not them, bred in our homes, endowed with goodness and decency. For if it is easy for them to murder, what about us? And so it is simpler and more comfortable not to hear. We do not listen to the angry words that cascade forth from their lips, wishing only that they would calm down, be reasonable, get some help, and go away. We, the deformed, brand our prophets as madmen. We cast them into the desert. And this is why so many veterans are estranged and enraged. This is why so many succumb to suicide or addictions.

For full article, see: http://www.truthdig.com/report/item/20090601_war_is_sin/

Memory, War, and the Memory of War

Memory, War, and the Memory of War

Louis Bickford, International Center for Transitional Justice

Memorial Day is meant to remind us of the hardship of war, and on this Memorial Day I find myself asking how we will remember the “war on terror.” What will our children’s children know about this period?

We choose in the present how future generations will remember the past. One of the great contributions of the human rights movement is showing that how we remember and memorialize trauma in the past — torture under brutal regimes in Argentina or during the apartheid era of South Africa, the evil committed during the Holocaust — can help prevent abuses in the future.

What does it mean to choose how to remember? Memories come flooding back, often unwilled, sometimes unwelcomed. The raw material of memory resembles dreams, uncontrolled and full of non-sequiturs. But consider the terrible affliction of “Funes the Memorious,” a character in a Jorge Luis Borges short story. He remembers everything, every shadow on every leaf on every tree, and he is thus immobilized and must sit in the dark to avoid sensory experience.

In real life, societies, like individuals, cannnot remember everything. We organize collective memory, purposefully or not. Imagining the future, we may choose to remember the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, for example, more in terms of heroism than error, since that is the tendency of all nations. We may remember the irreparable loss of life of those who went to fight, and we will think about their families and the suffering they endured. Our national memory may focus on the deaths of the Americans, in the same way that our memories of Vietnam focus largely on American causalities.

Will we remember that there was a place called Abu Ghraib on the dusty outskirts of Baghdad, and that torture took place there, for which we were responsible? Will we remember that we acquiesced to a terrible policy put forward by our leaders and with the endorsement of many — Democrats, Republicans, journalists, legal scholars — that allowed for us to ignore international and American law prohibiting torture?

If we care about the future, we must, first, clarify the truth. Second, we must find ways of clearly condemning torture wherever and whenever it was committed. Third, we must take steps so that we remember our rejection of those acts. Our thinking about future memory is one way of preventing torture in the future.

We need to know the full truth, including who among us was complicit in allowing this to happen, even if it means looking inward to our own communities. Why did not more of us protest more loudly and sooner? Why did so many permit government lawyers to pervert the law for dubious ends, making a mockery out of the idea of reasonable legal interpretation?

We must engage in a serious inquiry and introspection with the goal of accountability. Journalists and scholars should continue their investigative research and analysis of what has transpired. A nonpartisan commission of inquiry should also be a part of this picture, as should the continued declassification of government documents. We should also help others transform Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo, and other sites of torture into sites of learning for the future. Seen from the perspective of memory, fair trials of those most responsible for wrong-doing are essential. The documents produced by trials would be vital elements of a true historical record. And trials are the strongest way of representing moral condemnation of wrongful behavior.

Friedrich Nietzsche, the German philosopher, identified three forms of history: antiquarian, monumental, and critical. The first sees history as quaint, curious, distant and irrelevant to our current lives. The second celebrates victory, heroism and tragedy in the past as precursors to current glory. The third suggests an engagement with the memory of the past, seeing the linkages between past, present and future and seeking to understand them.

Former Vice-President Dick Cheney is seeking to convince Americans that torture was justified. It is clear that he is interested in how this period is remembered; he is speaking both to us and to our progeny. He wants the history books and national memory to validate his time in office, and he is making active attempts to guarantee that they do. He wants to create a monumental history of the period.

If former officials succeed in making us forget that there was torture and that it was contrary to our values, they will establish impunity for the present and also for the future. That must not be allowed to happen. Extreme violations of human rights in any context, including a war, are too important to forget. We want future generations to remember that we insisted on accountability for them. Those are good reasons to have Memorial Day.

Dr. Louis Bickford, a political scientist, is Director of the Memory, Memorials, and Museums program at the International Center for Transitional Justice (www.ictj.org), an international non-governmental organization with offices throughout the world. The ICTJ assists countries pursuing accountability for past mass atrocity or human rights abuse. The Center works in societies emerging from repressive rule or armed conflict, as well as in established democracies where historical injustices or systemic abuse remain unresolved.

Dr. Bickford’s essay is from The Huffington Post, where it was posted May 21, 2009, and was reprinted in PeaceMeal, May/June 2009.

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)