What the C.I.A.’s torture program looked like to the tortured

GUANTÁNAMO BAY, Cuba — Drawings done in captivity by the first prisoner known to undergo “enhanced interrogation” by the C.I.A. portray his account of what happened to him in vivid and disturbing ways. One shows the prisoner nude and strapped to a crude gurney, his entire body clenched as he is waterboarded by an unseen interrogator. Another shows him with his wrists cuffed to bars so high above his head he is forced onto his tiptoes, with a long wound stitched on his left leg and a howl emerging from his open mouth. Yet another depicts a captor smacking his head against a wall.

They are sketches drawn in captivity by the Guantánamo Bay prisoner known as Abu Zubaydah, self-portraits of the torture he was subjected to during the four years he was held in secret prisons by the C.I.A. Published recently for the first time, they are gritty and highly personal depictions that put flesh, bones and emotion on what until now had sometimes been portrayed in popular culture in sanitized or inaccurate ways: the torture techniques used by the United States in secret overseas prisons during a feverish pursuit of Al Qaeda after the September 11, 2001, attacks.

In each illustration, Mr. Zubaydah — the first person to be subject to the interrogation program approved by President George W. Bush’s administration — portrays the particular techniques as he says they were used on him at a C.I.A. black site in Thailand in August 2002. They demonstrate how, more than a decade after the Obama administration outlawed the program and then went on to partly declassify a Senate study that found the C.I.A. lied about both its effectiveness and its brutality, the final chapter of the black sites has yet to be written.

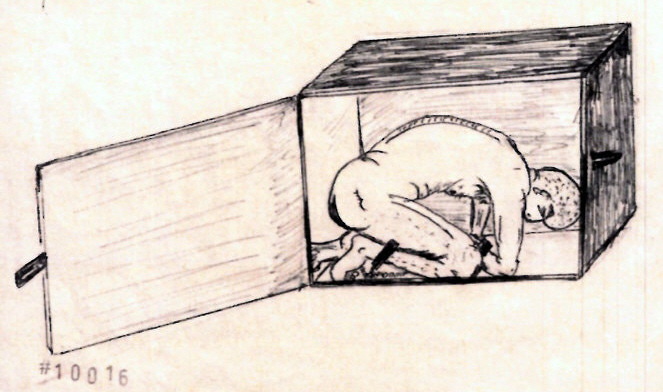

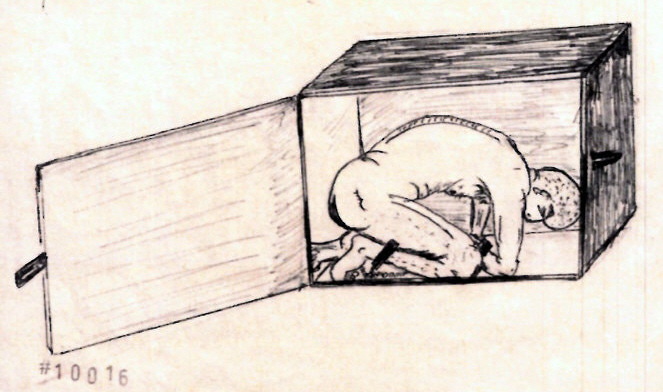

Image drawn by Abu Zubaydah shows how the C.I.A. applied an approved torture technique in a “cramped confinement” box.

Mr. Zubaydah, 48, drew them last year at Guantánamo for inclusion in a 61-page report, “How America Tortures,” by his lawyer, Mark P. Denbeaux, a professor at the Seton Hall University School of Law in Newark, and some of Mr. Denbeaux’s students. The report uses firsthand accounts, internal Bush administration memos, prisoners’ memories, and the 2014 Senate Intelligence Committee report to analyze the interrogation program.

The program was initially set up for Mr. Zubaydah, who was mistakenly believed to be a top Qaeda lieutenant. He was captured in a gun battle in Faisalabad, Pakistan, in March 2002, gravely injured, including a bad wound to his left thigh, and was sent to the C.I.A.’s overseas prison network.

After an internal debate over whether Mr. Zubaydah was forthcoming to F.B.I. interrogators, the agency hired two C.I.A. contract psychologists to create the now-outlawed program that would use violence, isolation and sleep deprivation on more than 100 men in secret sites, some described as dungeons, staffed by secret guards and medical officers.

Descriptions of the methods began leaking out more than a decade ago, occasionally in wrenching detail but sometimes with little more than stick-figure depictions of what prisoners went through. But these newly released drawings depict specific C.I.A. techniques that were approved, described and categorized in memos prepared in 2002 by the Bush administration, and capture the perspective of the person being tortured, Mr. Zubaydah, a Palestinian whose real name is Zayn al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn.

He was the first person known to be waterboarded by the C.I.A. — he endured it 83 times — and was the first person known to be crammed into a small confinement box as part of what the Seton Hall study called “a constantly rotating barrage” of methods meant to break what interrogators believed was his resistance.

Subsequent intelligence analysis showed that while Mr. Zubaydah was a jihadist, he had no advance knowledge about the 9/11 attacks, nor was he a member of Al Qaeda. He has never been charged with a crime, and documents released through the courts show that military prosecutors have no plans to do so.

He is still held at the base’s most secretive prison, Camp 7, where he drew the sketches not as artwork, whose release from Guantánamo is now forbidden, but as legal material that was reviewed and cleared — with one redaction — for inclusion in the study.

– edited from The New

York Times, Dec. 4, 2019

PeaceMeal, January/February 2020

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)

Senate report on CIA torture is one step closer to disappearing

The CIA inspector general’s office — the agency’s internal watch-dog — has acknowledged it “mistakenly” destroyed its only copy of a mammoth Senate torture report at the same time lawyers for the Justice Department were assuring a federal judge that copies of the document were being preserved. While another copy of the report exists elsewhere at the CIA, the erasure of the document by the office charged with policing CIA conduct has alarmed the U.S. senator who oversaw the torture investigation and reignited a battle over whether the full report should ever be released.

In what one intelligence community source described as a series of errors straight “out of the Keystone Cops,” CIA inspector general officials deleted an uploaded computer file with the report and then accidentally destroyed a disk that also contained the document, filled with thousands of secret files about the CIA’s use of so-called “enhanced” interrogation methods.

The destruction of a copy of the sensitive report was reported to the federal judge who, at the time, was overseeing a lawsuit by the American Civil Liberties Union seeking access to the still-classified document under the Freedom of Information Act. According to the ACLU brief, the document “describes widespread and horrific human rights abuses by the CIA” and details the agency’s “evasions and misrepresentations” to Congress, the courts and the public.

The CIA’s chief of public affairs, Dean Boyd, emphasized that another unopened computer disk with the full report has been, and still is, locked in a vault at agency headquarters. “I can assure you that the CIA has retained a copy,” he wrote in an email.

The 6,700-page report, the product of years of work by the Senate Intelligence Committee, contains meticulous details, including original CIA cables and memos, on the agency’s use of waterboarding, sleep deprivation and other aggressive inter-rogation methods at “black site” prisons overseas. The full three-volume report has never been released, but a 500-page executive summary was released in December 2014 by Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D.-Calif.), the committee’s outgoing chair. It concluded that the CIA’s interrogations were far more brutal than the agency had publicly acknowledged and produced often unreliable intelligence. The findings drew sharp dissents from Republicans on the panel and from four former CIA directors.

Ironically in light of the inspector general’s actions, the intelligence committee’s investigation was triggered by the CIA’s admission in 2007 that it had destroyed another key piece of evidence — hours of videotapes of the waterboarding of two “high value” detainees, Abu Zubaydah and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri.

In light of a U.S. Court of Appeals ruling in May that the document is not subject to the Freedom of Information Act, there are new questions about whether it will ever be made public, or even be preserved. To ensure the document was circulated widely within the government, and to preserve it for future declas-sification, Feinstein, in her closing days as chair of the Senate committee, instructed that computer disks containing the full report be sent to the CIA and its inspector general, as well as the other U.S. intelligence and law enforcement agencies. But her successor, Republican Sen. Richard Burr of North Carolina, quickly asked for all of the disks to be returned, even threatening at one point to send a committee security officer to retrieve them. He contended they are congressional records that were never intended for executive branch, much less public, distribution.

The administration, while not complying with Burr’s demand to return the disks, has essentially sided with him against releasing them to the public.

A Justice Department spokesman said on April 15 that, since the inspector general’s office is, by statute, a “unit” of the CIA, and the agency still had its copy, “the status quo … was preserved.” But Feinstein, in a separate letter to Attorney General Loretta Lynch, took a different view: She asked that the Justice Department “notify the federal courts” involved in the Freedom of Information Act litigation about the destruction.

In the meantime, Feinstein, joined by Democratic Sen. Patrick Leahy of Vermont, petitioned David S. Ferriero, the chief of the National Archives, to formally declare the report a “federal record” that must be preserved “in the public interest” under the Federal Records Act. In an April letter, the senators expressed concerns that federal agencies might destroy their copies of the report. “No part of the executive branch has ruled out destroying or sending back the full report to Congress after the conclusion of the current FOIA litigation,” they wrote.

A similar point was raised by more than 30 advocacy groups who noted in a separate letter to Ferriero in April that the archivist had a duty to act whenever there was a threat that government records are at risk of “unauthorized destruction.” Ferriero on April 29 wrote back to Feinstein that he would not rule on the question until the FOIA court case is concluded.

Feinstein, now the vice chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee, wrote CIA Director John Brennan asking him to “immediately” provide a new copy of the full report to the inspector general’s office. “Your prompt response will allay my concern that this was more than an ‘accident,’” Feinstein wrote.

A three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled in May that the torture report is a congressional document not subject to the FOIA, under the terms of a 2009 letter by which the Senate panel had received access to CIA files. The judges did write, however, that the executive branch does have “some discretion to use the full report for internal purposes.”

The incident is the latest twist in the ongoing battle over the report, and comes in the midst of a charged political debate over torture. Likely Republican Party nominee Donald Trump has vowed to resume such methods — “and a lot more” — in the war against the Islamic State.

– edited from articles

by Michael Isikoff, Chief Investigative Correspondent, Yahoo News, May 16 & 20 2016

PeaceMeal, May/June 2016

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)

CIA torturers should sue the federal government

It’s always the people lowest on the social ladder who face the worst of America’s vicious criminal justice system. Consider the torturers at Abu Ghraib. A policy designed and implemented at the very highest levels of the Bush administration was blamed on a few low-level scapegoats. Hence, while a few actual torturers — the people swinging the rubber mallets, locking the handcuffs, pouring lungs full of water, and so on — were punished, the vast majority of the architects of torture got off scot-free. It seems too much of the American power structure was implicated to do more than punish low-level soldiers who tortured — people like Lynndie England and Charles Graner.

As a result, aside from the Senate torture report (most of which still has not been released) and a few independent studies, there has been no real accounting or reckoning with the fact of American torture. But despite the lack of legal punishment, most American torturers probably suffer terribly from what they have done. Research shows that, for normal people, the act of torture psychologically harms the torturer almost as much as it does the victim.

Professor Shane O’Mara, in his recent book Why Torture Doesn’t Work, summarizes much empirical work on the effects of torture on those who carry it out. Humans are social creatures, and we have empathic systems hard-wired into our perceptive apparatus. Humans wince when they see others receive electric shocks. They cry when they see animals hurt. Formal studies in which people are made to watch another person endure a small pain are helpless to prevent that system from firing — even if they have been informed that the person has been anesthetized and cannot feel anything.

The empathic system is why it’s so disturbing to see someone be badly injured. Torturers, who are deliberately suppressing that system to inflict grievous harm on a helpless person, will likely suffer worse consequences. “Requiring individuals to torture another human being as part of their employment would seem to present a real and meaningful danger to the long-term well-being of employees,” O’Mara writes. And indeed, accounts of veteran torturers bear this out.

The military and the CIA sold the torture regime to the country and themselves as part of an allegedly necessary program to keep the nation safe. Except it turns out it was all for nothing. As is now extremely well-established, the torture program was worthless for interrogation; it was just a source of suffering and death and a blight on America’s moral reputation. That in turn means that the psychological harm endured by all the veteran torturers was completely pointless. And, indeed, many report suffering crippling guilt.

Don’t get me wrong. The act of torture is still a moral abomination. Torturers deserve condemnation for immoral acts at the least. But worse by far are the high-level politicians, bureaucrats, and legal hacks — people like Dick Cheney, John Yoo, Donald Rumsfeld and David Addington — who designed the torture program and forced it into use over the loud objections of much of the security apparatus. For them, torture was a way to demonstrate toughness and nothing else, and they abused the patriotism of soldiers and contractors to do it. Moreover, those far from the abuse do not suffer the psychological consequences.

– edited from an

article by Ryan Cooper, The Week, December 16, 2015

PeaceMeal Jan/February 2016

FBI agents accused of torturing U.S. citizen abroad can’t be sued

Federal agents who illegally detain, interrogate and torture American citizens abroad can’t be held accountable for violating the Constitution, a divided U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit ruled on October 23. The court rejected the lawsuit of a U.S. citizen who claimed the FBI trampled his rights for four months across three African countries while he was traveling overseas.

In so many words, the ruled that the plaintiff, Amir Meshal, couldn’t sue the federal government for such violations and punted the issue to someone else. “If people like Meshal are to have recourse to damages for alleged constitutional violations committed during a terrorism investigation occurring abroad, either Congress or the Supreme Court must specify the scope of the remedy,” Judge Janice Rogers Brown wrote for the majority.

Meshal’s case had drawn support from a number of law professors, along with present and former United Nations special rapporteurs on torture, who had hoped the court would help clarify when the U.S. can be made to answer for abuses abroad.

At issue in the case was a 1971 decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, Bivens v. Six Unknown Unnamed Agents, which found for the first time that the Constitution allows citizens to hold liable federal officials who violate their rights — even if Congress hadn’t expressly passed a law to that effect.

In subsequent decisions, however, Bivens liability has been greatly narrowed by the Supreme Court, and even more by lower courts interpreting those decisions.

In the current ruling, the D.C. appeals court dismissed Meshal’s case, based in large part on the view that the law offers him no help, and that courts are in no position to intervene — absent congressional or Supreme Court approval — where national security and foreign policy interests are at stake.

Judge Nina Pillard, who dissented in the case, pointed to “unspecified concerns” as precisely the reason courts should get involved in a case like this. Judges, after all, have “a particular responsibility to assure the vindication of constitutional interests” in the face of official misconduct — especially with increased U.S. involvement abroad. One can only hope the Supreme Court will hear her call.

– edited from an

article by Cristian Farias in The Huffington Post, October 23, 2015

PeaceMeal Jan/February 2016

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)