The IRC and Sesame Workshop bring hope and education to a generation of Syrian refugee children.

For the past seven years, the Middle East has been the epicenter of a global refugee crisis, with millions of children born into chaos. Many of these children, now refugees, lack a safe place to learn, to play and to heal. Some have been exposed to extreme violence and are at risk of toxic stress, a biological response to prolonged and severe adversity that disrupts a child’s brain development.

The International Rescue Committee and Sesame Workshop are leading a historic early childhood initiative that will bring hope and opportunity to children whose lives have been uprooted by the Syrian war. In December 2017, our partnership won the Mac-Arthur Foundation 100&Change competition, which awards $100 million to a program that has the potential to solve a critical problem of our time.

With this extraordinary investment, we are creating the largest early childhood intervention in the history of humanitarian response. We will do this by implementing programs and culturally relevant content that engages children. We will also provide learning tools and strategies for their parents and caregivers. Our initiative will serve as a model early childhood program that can be replicated in future humanitarian crises.

Maha bought her daughter books, supplies and new clothes to get her excited about starting school. But 8-year-old Hanadi was terrified. “She’s afraid either a bomb will destroy her classroom or someone will come and shoot her,” Maha says.

Many children share Hanadi's anxieties, stemming from their experiences and troubled memories. IRC teacher Amina Hussein Fneish says, “We are aware that these children have come from war. They have seen things that scared them. We, as teachers, have the responsibility to boost their confidence again. We work on preparing them to face the world and achieve what they want.”

IRC’s partnership with Sesame Workshop aims to help millions of Syrian refugee children over the course of five years. We plan to reach 1.5-million children directly and close to 9.5 million via electronic and digital media — in Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria. The initiative aims to give parents, caregivers and educators the tools and skills they need to help children learn and overcome the trauma of conflict and displacement.

The International Rescue Committee is a global humanitarian aid, relief and development nongovernmental organization founded in 1933. See www.rescue.org.

– PeaceMeal, January/February 2019

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)

U.S. and its moral obligation to those at the border

Anne Gordon

The Hill, November 20, 2018

More than 1,500 men, women and children from the migrant caravan have arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border; half are girls and women. Most are fleeing violence and poverty. All are seeking a better life. While they wait at the border considering their options, perhaps it is time to consider ours.

Many of them have already endured untold suffering. Many migrant women have been victims of sexual and physical abuse and many more are victims of abuse along the way. Even the Trump administration has said that as many as 80 percent of women are raped on journeys north from Central America. Some are pushing baby strollers or carrying infants on their backs. For many, escape is a matter of life or death.

If they make it to the U.S., even if they claim asylum, their suffering does not end. I’m a lawyer, and this summer I went to the South Texas Family Residential Center, about 80 miles from the Mexico border, to help women with their asylum claims and to bear witness to the human cost of our border policies.

There, inside the jail, clients told me how they were locked up, sometimes still wet from a river crossing, in chain-link-fence cages called “la perrera” (the kennel), or in “la hielera” (the ice box), a freezing concrete room. They might sit there for days. One of my clients, a 16-year-old girl, was not allowed to hug her 9-year old sister because kids were not allowed to touch each other in the cages.

This summer many moms were told they’d never see their kids again. Some were compelled to sign documents in a language they didn’t understand, unknowingly waiving their right or their children’s right to claim asylum. One teenage girl told me of cradling a baby in their shared cage, both alone and scared without their mothers.

Eventually, the government might bring the parents and children to a family jail. The Dilley facility, where I was, is a series of portable buildings and tents in the Texas desert, nearly indistinguishable from the prison next door. It has fences, metal detectors and armed guards.

There, the mothers and children inside drink water from a jug that volunteers were told we should not drink from, the water having been polluted by fracking runoff. There was an outbreak of chickenpox while we were there, and we saw many kids who were sick or covered in rashes. The medical care was a joke; cases of medical incompetence abound, and one child has already died from a respiratory infection her family says was contracted, but never treated, in the facility. The Department of Homeland Security’s own experts issued a terrifying report on the harm to children it found in the centers.

If the migrants don’t make it to the U.S., they might spend days or weeks on the border, with U.S. officials turning them away before they can even reach the U.S. side of the bridge to claim asylum. There they will sit, with no shade, facilities, or food, until they make the perilous journey back to further danger or fall prey to the border cartels.

We can do better than this. First, we must allow those with asylum claims to make those claims in court with legal representation. Second, in the absence of flight risk, families should be released; ankle monitors are a cheap and effective way to keep track of people. Third, instead of sending nearly 6,000 troops to the border — who can't detain or deport immigrants anyway — we should send immigration officers who could keep families together, minimizing further trauma, while determining who is eligible to stay. Finally, we could offer aid to those who have risked everything at a chance for a better life.

We as a country must decide if traumatized moms, sick kids and baby jails are a good solution to the problem of the migrant caravan. It is true that not everyone in the group is a parent or a child; indeed, not everyone in the caravan is fleeing persecution and not everyone can stay. But for the sake of the parents, the children and the persecuted who are waiting at our border, we must choose policies that afford dignity, humanity and kindness.

Anne Gordon is a senior lecturing fellow at the Duke University School of Law.

– PeaceMeal, Nov/December 2018

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)

Parents now dealing with trauma of 3-year-old separated from father at the border

LOS ANGELES – In the living room of the one-bedroom Van Nuys apartment, the boy tried to explain in the words of a 3-year-old what happened to his father. “Papa cae en piso” (“Dad fell on the ground”), he said, turning briefly from a game on his mother’s phone.

Andriy Ovalle Calderon recounted the moment his father was restrained by Customs and Border Protection officers four months ago as he tried to cross into Texas illegally. The boy spent more than a month with a foster family in California before being released in April to his mother, who separately had turned herself in at a port of entry with her then 3-month-old son, Adrian.

Claudia Calderon has been allowed to stay with her mother-in-law while she waits for an immigration judge to hear her asylum claim. Her husband, Kristian Francisco Ovalle Hernandez, was deported to Guatemala.

At night, Andriy sometimes wakes up screaming in the bunk bed he shares with his mother and baby brother. When he started to wet the bed, Calderon put him back in diapers. Sometimes he throws his tiny body down on the floor, hands behind his back, acting out what happened to his father.

As federal agencies work on reuniting more than 2,000 families that remain apart, affected by the Trump administration’s “zero tolerance” immigration policy, many children are struggling to cope with the aftermath of the separations.

A 1-year-old taken from his father in November still wakes up crying, quieting only when his mother reassures him that she is there. In the first week of living in a Jefferson Park apartment, he would grab his mother’s legs and start to cry if someone came to visit.

“Those are absolutely classic signs of acute trauma,” said Dr. Amy Cohen, a child psychiatrist. As a volunteer at an immigrant respite center in McAllen, Texas, Cohen identified and helped traumatized children and adults separated in detention.

A child taken from a parent is flooded with anxiety, which quickly turns into panic, Cohen said. Children’s bodies and brains “are absolutely not built to withstand that level of stress.”

In several letters to the secretary of the Department of Homeland Security earlier this year, the American Academy of Pediatrics opposed separating parents and children, citing the trauma. “As children develop, their brains change in response to environments and experiences,” one letter said. “Fear and stress, particularly prolonged exposure to serious stress without the buffering protection afforded by stable, responsive relationships — known as toxic stress — can harm the developing brain and harm short- and long-term health.”

Robbed of a parent or a known caregiver, children are susceptible to “learning deficits and chronic conditions such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and even heart disease,”according to Dr. Colleen Kraft, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“There is nothing worse you can do to a child than taking their parent away,” Cohen said. “For a lot of these children ... even though they’re reunited with their parents, they now have implanted in their brain the fact that that parent can disappear at any moment, for no reason, without warning.”

Before the mother and son were reunited, Calderon said, she received from the Office of Refugee Resettlement a 50-page sponsor handbook that included details on what to expect when he came home. “Children who have a history of traumatic experiences often have nightmares, reliving the terrible things that happened to them,” one section said. “Some children refuse to go to bed and fight bedtime, some struggle to sleep because they are too afraid, and others may wet the bed.”

When Calderon picked Andriy up from International Christian Adoptions in Temecula on April 14, he called her “tia” (“aunt”). “I’m your mom,” she said in Spanish, crying as she held him.

Two months in the life of a child “is almost like two years in the life of an adult,” Cohen said. When Andriy was reacquainted with his mother, he possibly felt tricked and didn’t know whether to trust her, Cohen said. When the boy finally processed who Calderon was, he asked, “Y mi papi?” (“And my daddy?”)

Trying to keep a piece of his father, Andriy wants to wear the shoes his dad bought for him in Guatemala, even though they don’t fit any more.

“I want him to be happy again,” Calderon said. “He’s so little, and he has all of this in his head. ... I wish I could help him, but I can’t. Just my love and affection isn’t enough. He wants to be with his dad.”

Calderon wants to take Andriy to therapy, but said she doesn’t have the money. Instead she tries to console him the best she can, holding him tight every night the way his father used to.

When asked by a reporter about post-release services for children who are separated from a parent, a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services spokesman emailed a link regarding health and safety. “Once a child has been placed with a parent, relative, or other sponsor, the care and well-being of the child becomes the responsibility of that sponsor,” one paragraph said. “For the great majority of children who are released to sponsors, HHS does not provide ongoing post-release services.”

On a recent afternoon, Andriy ran around a park near his house, kicking around his World Cup soccer ball, taking breaks to hug his now 7-month-old brother cradled in his mother’s arms. When he saw a little girl crying on the slide, he comforted her, just like he does his mother whenever he catches her weeping over his father.

– edited from the Los

Angeles Times, July 5, 2018

PeaceMeal, July/August 2018

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)

Syrian refugees deserve freedom from slaughter

Kathleen Parker

We shouldn’t be surprised that many Americans fear the arrival of Syrian refugees in the wake of [November’s] Paris slaughter by jihadists, including at least one who appears to have entered Europe posing as a refugee. It’s pretty natural. Horrified by the savagery perpetrated on hundreds of civilians enjoying a Friday night, people think: No Syrians need apply here.

What they mean, of course, is no jihadists here. Agreed. There’s no guarantee that there are none here now, but why take a chance? If ever there were a case for abundant caution, it would seem to be now. Except for the fact that what is being proposed by several governors and politicians, including a few presidential candidates, is morally reprehensible, un-American and in some instances, legally untenable. If I may be blunt.

Fear does strange things to people. What happened to our admiration for Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s call to courage: “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself”?

House Republicans are calling for a pause in the Syria refugee program and for a new plan to handle the immigrants fleeing Syrian violence in light of the recent attacks in Paris.

By recent counts, at least 28 governors have vowed to not allow any of the 10,000 expected Syrian refugees to settle in their states. Legally, governors can’t prevent the free movement of people once they are granted refugee status by the federal government. So this is political posturing, unless the governors intend to take up arms against the feds, which would be especially interesting to the Islamic State.

Meanwhile, several contenders for the presidency have resorted to some rather bizarre interpretations of the Constitution, showing either a worrisome lack of understanding or some unremarkable “thinking.”

Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Tex.), who presumably knows better, has suggested that we should allow only Christian Syrians and not Muslim ones to enter the United States. Cruz promises to introduce legislation along these lines. As President Obama pointed out, we don’t do religious testing here.

Not to be outdone — ever — Donald Trump has said he would even consider shutting down mosques, presumably because they might be preaching un-American values. Where was he when Westboro Baptist Church was spewing hatred toward gays? Or when Terry Jones, pastor of the Dove World Outreach Center, wanted to burn Korans?

The great thing about America? We’ll let any old crank preach his own gospel from any fruit crate or mosque (though not on college campuses, where privileged children hide from mean ideas in “ safe spaces ”).

New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie (Rep.), apparently intent on displaying just how tough he is, said he wouldn’t even let in Syrian orphans under age 5. Both he and Ben Carson say they don’t trust our government to properly vet refugees.

Into this moral morass wanders at least one rational man, Sen. Lindsey Graham (Rep.-S.C.), who has suggested only that we temporarily pause our refugee program — perhaps to recover from the horror and clear our minds. Being lowest in the polling frees one to be rational about this.

Obviously, political polling indicates that the Republican base, already unhappy about ineffective immigration policies, approves of such draconian measures. GOP voters figure if the government can’t prevent millions of people from entering the United States illegally or staying past their visas, then how can we be sure it won’t let in a few jihadists among the refugees?

It’s a fair question that deserves a serious, responsible answer. But it is unfair to label people as anti-immigrant or Islamaphobic when their legitimate concerns are about rule of law and staying alive. Anyone who isn’t concerned about the promised Islamic caliphate at the point of a spear, possibly with your head on it, has better drugs than I do.

From Turkey on Nov. 16, President Obama defended his policy in Syria and said he won’t engage in another ground war in the Middle East. Obviously referring to our attempt to impose democracy in Iraq, he said that freedom from ideological extremism has to come from within “unless we’re prepared to have a permanent occupation of these countries.”

Only the most hawkishly delusional would disagree with this assessment. But freedom from slaughter is something else, is it not? Thus far, more than 200,000 Syrians have died. How many does it take to bestir our moral outrage? When does someone else’s civil war become our problem? And, pointedly, does helping victims by killing Muslim “warriors” reduce or increase the likelihood that radicalism will cease or decrease?

These are all tough questions without clear answers, but our values and principles can help guide us through deliberations. Once we retreat from those values, we will have compromised, and potentially lost, what there is left to protect.

Kathleen Parker is a Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist for The Washington Post, where this column was published Nov. 17, 2015 and reprinted in PeaceMeal, Nov/December 2015.

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)

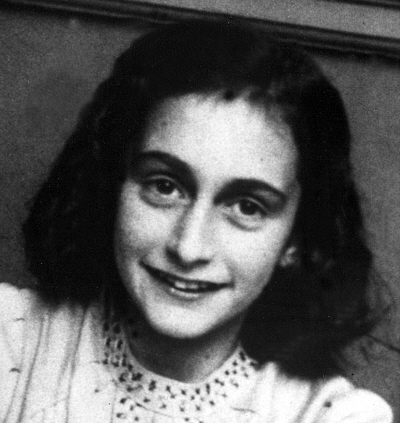

Anne Frank and her family were denied entry as refugees to the United States

Many

have noted the historical parallels between the current debate over Syrians seeking refuge

in the United States and the plight of European Jews fleeing German-occupied territories

on the eve of World War II. Among the many who tried — and failed — to escape

Nazi persecution were Otto Frank and his family, which included wife Edith and daughters

Margot and Anne.

Many

have noted the historical parallels between the current debate over Syrians seeking refuge

in the United States and the plight of European Jews fleeing German-occupied territories

on the eve of World War II. Among the many who tried — and failed — to escape

Nazi persecution were Otto Frank and his family, which included wife Edith and daughters

Margot and Anne.

The Frank family relocated from Germany to the Netherlands in 1934. In 1940, Germany attacked and occupied the Netherlands.

Prior to April 1941, Otto Frank’s business in the Netherlands was still going well. His family was comfortable, and some of the most restrictive moves made against Jews there hadn’t yet been enacted. Hence, he preferred the nuisances that encumbered an otherwise comfortable life under Nazi occupation to the insecurity of life as a double refugee, even if a new country could be found.

Frank tried relatively late to obtain visas to the United States, an ultimately doomed process laid bare in documents unearthed in 2007. The tortuous process involved sponsors, large sums of money, affidavits and proof of how their entry would benefit America. Edith Frank’s brothers stepped in to help; they had already come to the United States and were willing to supply affidavits of support. Even Otto Frank’s high-level connections within American business and political circles weren’t enough to secure safe passage for his family. The moment the Franks and their American supporters overcame one administrative or logistical obstacle, another arose.

By June 1941, with more than 300,000 names on the waiting list to receive an immigration visa to the United States, most U.S. consulates in German-occupied territories had closed or were closing. Otto Frank would have had to go to Spain or Portugal, legally, to apply at consulates there. But as the Frank family filed paperwork, immigration rules were changing, and attitudes in the United States toward immigrants from Europe were becoming increasingly suspicious. The American government was making it harder for foreigners to get into the country — and the Nazis were making it difficult to leave.

With the new immigration regulations, Otto Frank concluded that the prospect of getting into the U.S. directly was dim. So he turned to Cuba as a possible refuge. Despite the considerable hardships and expense — it usually cost about $2,500 per person to obtain a visa — Otto Frank managed to get a Cuban visa for himself on December 1, 1941. Ten days later, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States, and Frank’s visa was canceled.

The Frank family went into hiding in 1942, a day after Margot Frank received a Nazi order to go east to a labor camp and a month after Anne Frank received a diary for her 13th birthday. Their hiding place was eventually betrayed, and they were all arrested and sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp. Otto Frank was the only member of the family to survive. Edith Frank died of starvation. Anne Frank and her sister Margot were moved to Bergen-Belsen, where they died in an epidemic of typhus shortly before the camp was liberated.

“It’s difficult in times like these: ideals, dreams and cherished hopes rise within us, only to be crushed by grim reality,” 15-year-old Anne Frank wrote in 1944 in her diary. “It’s a wonder I haven’t abandoned all my ideals, they seem so absurd and impractical. Yet I cling to them because I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart.”

– edited from The

Washington Post, November 25, 2015

PeaceMeal, Nov/December 2015

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)

Millions facing misery in worst refugee crisis since World War II

Kareem Shaheen

Kareem Shaheen

BEIRUT – Millions of refugees have been condemned to a life of misery in the worst displacement crisis since World War II, a leading human rights organization has said in a scathing report that blames world leaders’ neglect for the deaths of thousands of civilians fleeing wars in the Middle East and Africa.

“We are witnessing the worst refugee crisis of our era, with millions of women, men and children struggling to survive amidst brutal wars, networks of people traffickers, and governments who pursue selfish political interests instead of showing basic human compassion,” said Salil Shetty, Amnesty International’s secretary general, in a statement. “The refugee crisis is one of the defining challenges of the 21st century, but the response of the international community has been a shameful failure.”

The report, titled “The Global Refugee Crisis: A Conspiracy of Neglect,” places a particular focus on the Syrian crisis. Almost 4 million people displaced from Syria have registered with the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees. The burden has fallen almost entirely on the shoulders of neighboring states, who host 95 percent of the refugees. In Lebanon, one in five people is a Syrian refugee, the equivalent per capita of the United States hosting 64 million refugees.

With its infrastructure stretched beyond the breaking point and its government in a state of disarray, Lebanon has imposed a series of restrictions on the entry of refugees that has led to an 80 percent drop in new registrations compared with last year, despite the continued ferocity of the Syrian civil war.

The report concluded that the countries hosting Syrian refugees have received “almost no meaningful international support”, with the U.N.’s humanitarian appeal to cover the costs of caring for the refugees receiving less than one-fourth of the necessary funds. In Turkey, border guards used water cannons to push back a fresh influx of refugees fleeing the fighting between Islamic State militants and Kurdish militias near the long border with Syria.

Amnesty criticized the international community for similarly failing to respond to massive displacement crises in sub-Saharan Africa, where there are an estimated 3 million refugees, including hundreds of thousands who have fled conflicts in Nigeria, South Sudan, the Central African Republic and Burundi in recent years.

On the Mediterranean migrant crisis, Amnesty called on European nations to share the burden of resettling refugees, and said the scaling back of Operation Mare Nostrum (Our Sea) — the Italian effort to handle asylum seekers fleeing to Europe by boat — had contributed to the increase in the number of people drowning. About 3,500 people died while trying to cross the Mediterranean to Europe in 2014, with 1,865 dying this year so far. The majority of those fleeing by boat are Syrians.

In southeast Asia, 300 refugees and migrants have died at sea due to starvation, dehydration and abuse by boat crews, with Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand initially refusing to allow boats carrying migrants to land, putting many at risk. Amnesty castigated the Australian government in particular for “harsh, humiliating” conditions in which asylum seekers are kept when they attempt to reach the country.

Amnesty estimated the number of displaced people globally to be above 50 million, a crisis greater in magnitude than any since World War II. The rights group called on states to resettle 1.5 million refugees over the next five years, prioritize saving the lives of displaced people over domestic immigration policies, create a refugee fund, hold a global summit to deal with the crisis, and ratify the U.N.’s refugee convention.

– The Guardian (U.K.), June 15, 2015

PeaceMeal, July/August 2015)

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.)