Why the atomic

bombing of Hiroshima would be illegal today

Katherine E. McKinney, Scott

D. Sagan & Allen S. Weiner

The archival record makes

clear that killing large numbers of civilians was the primary purpose of the atomic

bombing of Hiroshima. Destruction of military targets and war industry was a secondary

goal and one that “legitimized” the intentional destruction of a city in the

minds of some participants.

The

atomic bomb was detonated over the center of Hiroshima. More than 70,000 men, women and

children were killed immediately. The munitions factories on the periphery of the city

were left largely unscathed. Such a nuclear attack would be illegal today. It would

violate three major requirements of the law of armed conflict codified in Additional

Protocol I of the Geneva Conventions: the principles of distinction, proportionality and

precaution.

In his

first radio address after the bombing of Hiroshima, President Harry S. Truman claimed that

“the world will note that the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, a military

base. That was because we wished in this first attack to avoid, insofar as possible, the

killing of civilians.”

President

Truman’s statement was misleading in two important ways. First, although Hiroshima

contained some military-related industrial facilities, an army headquarters, and troop

loading docks, the vibrant city of over a quarter of a million men, women and children was

hardly “a military base.” Indeed, less than 10 percent of the individuals killed

on August 6, 1945 were Japanese military personnel. Second, the U.S. planners of the

attack did not attempt to “avoid, insofar as possible, the killing of

civilians.” On the contrary, both the Target Committee (which included Robert

Oppenheimer and Maj. Gen. Leslie Groves of the Manhattan Project) and the higher-level

Interim Committee (led by Secretary of War Henry Stimson) sought to kill large numbers of

Japanese civilians in the attack. The Hiroshima atomic bomb was deliberately detonated

above the residential and commercial center of the city to magnify the shock effect on the

Japanese public and leadership in Tokyo.

What were

the legal considerations and moral reasoning used in 1945 to justify the A-bomb attack on

Hiroshima? Could such considerations and reasoning be used today?

The law

of armed conflict regarding aerial bombardment was not well-developed during World War II,

prior to the adoption of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the 1977 Additional Protocols.

There was no formal legal analysis of the attack options contemplated in 1945.

Nonetheless, intuitive moral concerns and background legal principles were often raised in

the secret discussions among American military officers, nuclear laboratory scientists,

and high-level political leaders planning the attack.

What the

archival record makes clear is that such concerns were muted and, when expressed, were

rejected and then rationalized away. The desire to avoid the U.S. military casualties

expected in the planned invasion of Japan, combined with a desire for vengeance against

Emperor Hirohito and the Japanese, overwhelmed legal concerns and moral qualms about

killing civilians on a massive scale.

Such a

nuclear attack would be illegal today. It would violate three major requirements of the

law of armed conflict codified in Additional Protocol I of the Geneva Conventions: to not

intentionally attack civilians (the principle of distinction or noncombatant immunity); to

ensure that collateral damage against civilians is not disproportionate to the direct

military advantage gained from the target’s destruction (the principle of

proportionality); and to take all feasible precautions to reduce collateral damage against

civilians (the precautionary principle).

The role

of lawyers in U.S. military planning has grown enormously in recent decades. All military

plans, from tactical operations to nuclear war options, are now reviewed by members of the

Judge Advocate General’s Corps (JAGs). This ensures that any contemplated nuclear

first strike would receive a formal legal review today, and that such legal objections

would be raised. Yet there is no guarantee that a future U.S. president would follow the

law of armed conflict. That is why we need presidents who care about law and justice in

war and that is why we need senior military officers to fully understand the law and

demand compliance.

The

history of the “decision” to drop the atomic bomb has been told many times, but

what has been underplayed is how concerns about ethics and law were invoked in a manner

that had little impact on the targeting of Hiroshima. Truman’s speech raised Japanese

violations of international law as a justification for dropping the bomb and displayed his

retributive leanings: “Having found the bomb, we have used it. We have used it

against those who attacked us without warning at Pearl Harbor, against those who have

starved and beaten and executed American prisoners of war, against those who have

abandoned all pretense of obeying international laws of warfare.”

The

international law of armed conflict, however, provided scant guidance on aerial

bombardment before and during World War II. Two committees — the Target Committee and

the Interim Committee — were convened in the Spring of 1945 to advise U.S. leaders on

use f the atomic bomb. At its May 1945 meetings at Los Alamos, the Target Committee agreed

that destruction of the selected target should succeed in “obtaining the greatest

psychological effect against Japan.” The prioritization of maximizing the bomb’s

“psychological impact,” while still wanting to include destruction of military

targets, was also present in the Interim Committee meetings later that month. According to

the minutes of the May 31 meeting, War Secretary Stimson concluded “that we could not

give the Japanese any warning; that we could not concentrate on a civilian area; but that

we should seek to make a profound psychological impression on as many of the inhabitants

as possible.” This was an endorsement of terror bombing with a legal veneer.

Officials

in Washington and Los Alamos had discussed the idea of a “demonstration strike”

— providing a warning and then dropping the bomb on an uninhabited area or purely

military target like a navy base — with many objections raised: if the bomb did not

detonate, Japan would be not demoralized, but encouraged to continue fighting; the

Japanese might place allied prisoners of war at the site. Moreover, the bombs had been

designed to be dropped from 30,000 feet and explode in the air, rather than closer to the

ground, in order to maximize target damage.

The

prioritization of civilian targeting was made explicit by General Groves in his memoirs:

“[T]he targets chosen should be places the bombing of which would most adversely

affect the will of the Japanese people to continue the war. Beyond that, they should be

military in nature, consisting either of important headquarters or troop concentrations,

or centers of production of military equipment and supplies.”

Those

statements make clear that killing large numbers of civilians was the primary purpose of

the attack; destruction of military targets and war industry was a secondary goal and one

that “legitimized” the intentional destruction of a city in the minds of some

participants. In fact, the crew of the Enola Gay, who were permitted to pick the target

point, chose the easily recognizable Aioi Bridge at the center of Hiroshima.

Could a

nuclear attack like the one that destroyed Hiroshima be legally justified today? What

advice should a JAG lawyer provide to a senior officer if a president issued an order to

drop a nuclear bomb on a city in Iran or North Korea or another foreign country, in an

attempt to coerce its government into accepting unconditional surrender by killing large

numbers of civilians?

First,

the president should be told that, although the United States did not ratify and is

therefore not a party to, Additional Protocol I of the Geneva Convention, the United

States government has long accepted that the principles of distinction, proportionality,

and precaution codified in Protocol I reflect binding international law and thus are legal

obligations.

In

addition, the Obama Administration clearly stated in 2013 that these obligations apply to

nuclear weapons: “[A]ll plans must also be consistent with the fundamental principles

of the Law of Armed Conflict. Accordingly, plans will, for example, apply the principles

of distinction and proportionality and seek to minimize collateral damage to civilian

populations and civilian objects. The United States will not intentionally target civilian

populations or civilian objects.” The Trump administration’s 2018 Nuclear

Posture Review (NPR) reaffirmed the U.S. commitment to “adhere to the law of armed

conflict” in any “initiation and conduct of nuclear operations.”

Moreover,

the Defense Department’s Law of War Manual specifically precludes attacks designed to

diminish “the morale of the civilian population and their support for the war

effort.” Senior officers would be legally required to disobey a president’s

order to intentionally target the center of a city as “manifestly” or

“patently” illegal.

A nuclear

strike against a legitimate military target could be legal only if it met all three

criteria: no intentional targeting of civilians, absence of disproportionate collateral

damage, and with all feasible precautions made to reduce collateral damage.

We hope,

but cannot know with certainty, that humanitarian principles and the law of armed conflict

would reign in a future conflict, even though they did not in 1945. Different presidents

clearly hold different views about the law of armed conflict, ranging from reverence to

flagrant disregard. Different presidents have different retributive proclivities.

President

Barack Obama called for a “moral awakening” in his 2016 speech in Hiroshima:

“The scientific revolution that led to the splitting of an atom requires a moral

revolution as well.” Then-candidate Donald Trump, in contrast, responded to

Obama’s Hiroshima visit by tweeting “Does President Obama ever discuss the sneak

attack on Pearl Harbor while he’s in Japan? Thousands of American lives lost.”

And Trump’s August 2017 threat to North Korea — “North Korea best not make

any more threats to the United States … They will be met with fire and fury like the

world has never seen” — was an echo of Truman’s statement, a thinly-veiled

nuclear first strike threat.

In future

wars, public pressures and the all too human instinct for retribution and revenge could

encourage a president to target foreign civilians or embrace disproportionate attacks. In

such dire scenarios, law must stay the hand of vengeance. At such moments, senior military

leaders must advise presidents on the law of armed conflict and insist on compliance.

Katherine

E. McKinney is a research assistant at the Center for International Security and

Cooperation (CISAC) at Stanford University. Scott D. Sagan is a Senior Fellow at CISAC and

serves as chairman of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences’ Committee on

International Security Studies. Allen S. Weiner is Senior Lecturer in Law and Director of

the Program in International and Comparative Law at Stanford Law School and Director of

the Stanford Center on International Conflict and Negotiation. He previously practiced

international law in the Legal Adviser’s Office of the U.S. Department of State.

Their

article is edited from Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, July 20, 2020, and was reprinted

in PeaceMeal, Sept/October 2020.

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is

distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the

included information for research and educational purposes.)

At Hiroshima Memorial, Obama says nuclear weapons ‘require a

moral revolution’

HIROSHIMA, Japan —

President Barack Obama laid a wreath at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial on May 27, telling an

audience that included survivors of America’s atomic bombing in 1945 that technology

as devastating as nuclear weapons demands a “moral revolution.”

Thousands

of Japanese lined the route of the presidential motorcade to the memorial in the hopes of

glimpsing Mr. Obama, the first sitting American president to visit the most powerful

symbol of the dawning of the nuclear age.

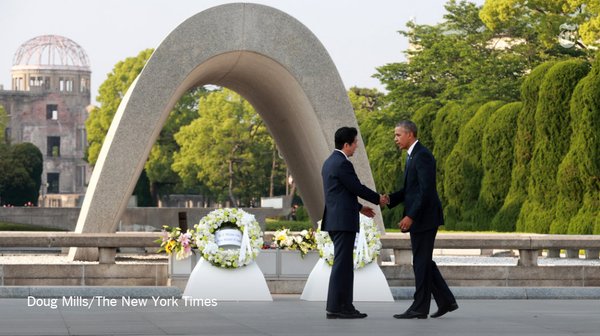

Photo caption: President Barack Obama and

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe shake hands after placing wreaths at the Hiroshima

Peace Memorial in memory of those who died from the atomic bombing. The iconic

“atomic dome,” the only building left standing near the hypocenter of the

A-bomb’s blast, is in the background.

Photo caption: President Barack Obama and

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe shake hands after placing wreaths at the Hiroshima

Peace Memorial in memory of those who died from the atomic bombing. The iconic

“atomic dome,” the only building left standing near the hypocenter of the

A-bomb’s blast, is in the background.

“Seventy-one

years ago, on a bright cloudless morning, death fell from the sky and the world was

changed,” Mr. Obama said in opening his speech at the memorial. Using the slow and

deliberate cadence that he uses only on the most formal occasions, Mr. Obama said the

atomic bombing of Hiroshima demonstrated that “mankind possessed the means to destroy

itself.”

He added

that, in the 71 years since the bombing, world institutions had grown up to help prevent a

recurrence. Still, nations like the United States continue to possess thousands of nuclear

weapons. And that is something that must change, he said.

In a

striking example of the gap between Mr. Obama’s vision of a nuclear weapons-free

world and the realities of eliminating them, a Pentagon census of the American nuclear

arsenal shows his administration has reduced the stockpile less than any other post-Cold

War presidency.

Noting

that far more primitive weapons than nuclear ones are causing widespread destruction

today, Mr. Obama called for humanity to change its mindset about war. “The world was

forever changed here, but today the children of this city will go through their day in

peace,” he said. “What a precious thing that is. It is worth protecting and then

extending to every child. That is a future we can choose, a future in which Hiroshima and

Nagasaki are known not as the dawn of atomic warfare but as the start of our own moral

awakening.”

Many

survivors long for an apology for an event that destroyed just about everyone and

everything they knew, and there were small demonstrations near the ceremony demanding an

apology. But Mr. Obama not only did not apologize, he made clear that Japan, despite being

a highly advanced culture, was to blame for the war, which “grew out of the same base

instinct for domination or conquest that had caused conflicts among the simplest

tribes.”

Still,

Mr. Obama’s homage to the victims and his speech were welcomed by many Japanese.

“I am simply grateful for his visit,” said Tomoko Miyoshi, 50, who lost 10

relatives in the Hiroshima attack and wept as she watched Mr. Obama on her cellphone.

Japanese

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, in his speech, said, “This tragedy must not be allowed to

occur again. We are determined to realize a world free of nuclear weapons.”

Mr.

Obama’s visit to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park had all the pomp and ceremony of a

state visit. With thousands in attendance and much of Japan watching on television, Mr.

Obama walked forward alone at the park and laid a wreath on a white pyramid. He paused

before the memorial’s cenotaph, his head bowed. A moment later, Mr. Abe approached

with his own wreath, which he laid beside Mr. Obama’s on another pyramid. After a

moment’s reflection, the two leaders shook hands — a clear signal of the

extraordinary alliance their two nations had forged out of the ashes of war.

The most

ironic aspect of the tableau was the off-camera presence of a military aide carrying the

“nuclear football,” a briefcase whose contents are to be used by the president

to authorize a nuclear attack.

In an

emotional moment afterward, Mr. Obama embraced and shook hands with survivors of the

devastating atomic blast on August 6, 1945. The first, 91-year-old Sunao Tsuboi, a

chairman of the Hiroshima branch of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers

Organizations, held hands with the president while he spoke to him for some time. He said

he told Mr. Obama that he will be remembered as someone who listened to the voice of a few

survivors, and urged him to return to meet more.

In

another poignant moment, Mr. Obama exchanged an embrace with Shigeaki Mori, 79, a

historian who was 8 years old when the atomic bomb exploded. Mr. Mori spent decades

researching the lives of American prisoners of war who were killed in the bombing. Mr.

Obama patted Mr. Mori on the back and hugged him as the survivor shed a few tears.

– edited from The New

York Times and The Associated Press

PeaceMeal, May/June 2016

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is

distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the

included information for research and educational purposes.)

The weight of a butterfly

The design the first atomic

bomb was frighteningly simple: One lump of a special kind of uranium, the projectile, was

fired at a very high speed into another lump of that same rare uranium, the target. When

the two collided, they initiated a nuclear chain reaction, and it was only a tiny fraction

of a second before the bomb exploded, forever splitting history between the time before

the atomic bomb and the time after.

Uranium

235 is the fissionable isotope that makes up only 0.7 percent of naturally occurring

uranium. To build an atomic bomb, you need uranium that is highly enriched in uranium 235.

The

uranium in the Hiroshima bomb was about 80 percent uranium 235. One metric ton of natural

uranium typically contains only 7 kilograms of uranium 235. Of the 64 kilograms of uranium

in the bomb, less than one kilogram underwent fission, and the entire energy of the

explosion came from only seven tenths of a gram of matter that was converted to energy.

That is about the weight of a butterfly.

–

edited from an article by Emily Strasser in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists,

February 25, 2015, and reprinted in PeaceMeal, May/June 2016. Her grandfather, George

Strasser, was a chemist who worked on separation of the uranium 235 isotope at Oak Ridge

during the Manhattan Project.

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is

distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the

included information for research and educational purposes.)

Takashi Nagai:

Mystic of Nagasaki (1908-1951)

“Our lives are of

great worth if we accept with good grace the situation Providence places us in, and go on

living lovingly.”

On the morning of August 9, 1945, Dr. Takashi Nagai was working in

his office at the medical center in Nagasaki, Japan. At 11:02 a.m. he saw a flash of

blinding light, followed by darkness, and then heard a crashing roar as his concrete

building, and his world, collapsed around him. What at first he took to be a direct hit on

the medical center was in fact the explosion of a plutonium-fueled atomic bomb five

hundred yards over the Urakami Cathedral.

On the morning of August 9, 1945, Dr. Takashi Nagai was working in

his office at the medical center in Nagasaki, Japan. At 11:02 a.m. he saw a flash of

blinding light, followed by darkness, and then heard a crashing roar as his concrete

building, and his world, collapsed around him. What at first he took to be a direct hit on

the medical center was in fact the explosion of a plutonium-fueled atomic bomb five

hundred yards over the Urakami Cathedral.

After

escaping from the rubble and receiving treatment for a severed carotid artery, Nagai

joined the rest of the hospital staff in treating the dazed and dying survivors. Given the

force and heat of the blast, he imagined that such a big bomb must have killed hundreds of

people. Only gradually did the extent of the destruction become clear. The bomb killed

60,000-70,000 persons and wounded many more.

In the

days ahead, Nagai witnessed scenes of horrifying suffering. The intense heat near the

epicenter of the blast had vaporized humans, leaving only the outlines of their shadows.

Hordes of blackened survivors, the skin hanging from their arms, desperately wandered the

streets crying for water. Nagai’s own two children had survived. But he found the

charred remains of his beloved wife in the ruins of their home, a rosary clasped

“among the powdered bones of her right hand.”

Such

circumstances might naturally prompt a range of reactions — madness, despair, or the

hunger for revenge. But in the days following the explosion Nagai, a devout Catholic,

instead expressed a most unexpected attitude — namely, gratitude to God that his

Catholic city had been chosen to atone for the sins of humanity.

In

arriving at this perspective, Nagai undoubtedly tapped into a spirituality deeply rooted

in the consciousness of Nagasaki’s Christian population. Since the time of the early

Jesuit missions, the city had been the center of Japanese Catholicism, and consequently

the scene of extensive martyrdom. Over time, Japanese Catholics had claimed a deep

identification with the cross of Christ and a conviction that atonement must come only at

the price of blood. Thus, it seemed natural for Nagai to pose the question: “Was not

Nagasaki the chosen victim, the lamb without blemish, slain as a whole burnt offering on

an altar of sacrifice, atoning for the sins of all the nations during World War II?”

Nagai was

himself a convert. Born on January 3, 1908, he became a Catholic in 1934. His conversion

was prompted by several influences, including the example of his fiancée, who belonged to

an ancient Catholic family; his reading of the mystic-scientist Blaise Pascal; and also a

period of deep soul-searching after the death of his mother.

Nagai

pursued a career in medicine, ultimately entering the field of radiology. In 1941 he was

found to be suffering from incurable leukemia, induced by his exposure to x-rays.

Nevertheless, he was able to continue his work, and in 1945 he had become the dean of

radiology at the University of Nagasaki.

In the

aftermath of the bombing on August 9, Nagai applied himself tirelessly to the medical

needs of the survivors. “Each life was precious. For all of these people the body was

a precious treasure.” But in the face of the enormity of the disaster, he gradually

began to see “that if I did not take a comprehensive view of this situation, we would

all be engulfed in the flames with the very victims we were bandaging and trying to

save.” As he carried on his work, he struggled to arrive at some understanding of the

meaning of this event, a meaning, ultimately, that he could discern only in relation to

the cross.

Nagai

found it remarkable that as a result of heavy clouds obscuring the originally intended

target city, Kokura, the bomb had been dropped that day on Nagasaki, an alternate target.

As a further result of clouds, the pilot had not fixed his target on the Mitsubishi iron

works as intended, but instead on the Catholic Cathedral in the Urakami district of the

city, home to the majority of Nagasaki’s Catholics. He noted that the end of the war

carne on August 15, feast of the Assumption of Mary, to whom the cathedral was dedicated.

All this was deeply meaningful. “We must ask if this convergence of events — the

ending of the war and the celebration of her feast —was merely coincidental or if

there was here some mysterious providence of God.”

Nagai

expressed these sentiments at an open-air requiem Mass just days after the bombing. While

his views were controversial, he provided consolation to many of the city’s Catholic

survivors, desperate to find some redemptive meaning in their terrible suffering:

We have disobeyed the law of love. Joyfully we have hated one

another; joyfully we have killed one another. And now at last we have brought this great

and evil war to an end. But in order to restore peace to the world it was not sufficient

to repent. We had to obtain God’s pardon through the offering of a great

sacrifice.... Let us give thanks that Nagasaki was chosen for the sacrifice.... May the

souls of the faithful departed, through the merey of God, rest in peace.

The

effects of radiation, combined with his previous illness, left Nagai an invalid, barely

able to leave his bed. He lived as a contemplative in a small hut near the cathedral ruins

in Urakami, writing books and receiving visitors. Increasingly, he came to believe that

Nagasaki had been chosen not only to atone for the sins of the war, but to bear witness to

the cause of international peace:

Men and women of the world, never again plan war! ... From this

atomic waste the people of Nagasaki confront the world and cry out: No more war! Let us

follow the commandment of love and work together. The people of Nagasaki prostrate

themselves before God and pray: Grant that Nagasaki may be the last atomic wilderness in

the history of the world.

Dr. Nagai

died on May 1, 1951, at the age of forty-three. His tombstone bears a simple epitaph from

the Gospel of Luke: “We are merely servants; we have done no more than our

duty.”

Article

from Robert Ellsberg, “All Saints: Daily Reflections on Saints, Prophets, and

Witnesses for Our Time” (1997, Crossroad Publishing, New York), 12-14. Quotations

from Takashi Nagai, “The Bells of Nagasaki,” translated by William Johnston

(1984, Kodansha International, Tokyo). Reprinted in PeaceMeal, July/August 2014.

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is

distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the

included information for research and educational purposes.)

Japanese man certified as double A-bomb survivor

TOKYO – A 93-year-old

Japanese man has become the first person certified as a survivor of both U.S. atomic

bombings at the end of World War II. Tsutomu Yamaguchi already had been a certified

“hibakusha,” or radiation survivor, of the Aug. 9, 1945, atomic bombing in

Nagasaki, and has now been confirmed as surviving the attack on Hiroshima three days

earlier as well, city officials said March 24.

Yamaguchi

was in Hiroshima on a business trip Aug. 6, 1945, when a U.S. B-29 dropped an atomic bomb

on the city. He suffered serious burns to his upper body and spent the night in the city.

He then returned to his hometown of Nagasaki just in time for the second attack.

“As

far as we know, he is the first one to be officially recognized as a survivor of atomic

bombings in both Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” Nagasaki city official Toshiro Miyamoto

said. “It’s such an unfortunate case, but it is possible that there are more

people like him.”

– PeaceMeal, July/August 2009

Iccho Itoh

1945-2007

Peace dove mourns

mayor nukes don't stop

felled by gun

~ Jim Stoffels

1995 letter from Mayor Iccho Itoh to World

Citizens for Peace

Nagasaki mayor

assassinated

Nagasaki Mayor Iccho Itoh, a

leader in the forefront of the global campaign to abolish nuclear weapons, was shot April

17, 2007, in front of his campaign office by a lone gunman and died hours later. The

assassin, Tetsuya Shiroo, shot Mayor Itoh from behind at close range after he got out of

his campaign car and fired another bullet into his back after he had fallen down,

according to police sources. The attack took place in front of many passers-by, and the

assailant was immediately subdued by Mr. Itoh’s supporters. Mr. Itoh was running for

his fourth term as mayor in elections to be held the following Sunday.

Mr. Itoh

arrived at Nagasaki University Hospital sometime after 8:00 pm in critical condition. His

heart and lungs had already stopped functioning, officials said. After placing Mr. Itoh on

a heart-lung machine, doctors proceeded with fours hours of emergency surgery in an

attempt to stop internal bleeding. However, Mr. Itoh, surrounded by his wife, Toyoko, and

other family members, died shortly after 2:00 am on April 18. Both bullets had ruptured

the heart of the 61-year-old mayor.

Investigators

said Tetsuya Shiroo, 59, was a senior member of Suishin-kai, a gang organization

affiliated with Japan’s largest crime syndicate. Police said Shiroo committed the

crime over a personal grudge against Mayor Itoh and the city government. Shiroo had

grievances against the city over an accident four years ago in which his car was damaged

by a pothole near a public works construction site. Shiroo was also reportedly upset with

the city for denying contracts to a construction company with which his gang was closely

linked. According to sources, Shiroo recently told other Suishin-kai gang members of his

unforgiving grudge against Mayor Itoh and threatened to kill him.

Born only

two weeks before the U.S. atomic bombing of Nagasaki on August 9, 1945, Mayor Itoh devoted

much of his life to making sure that nuclear weapons would never be used again. Since

taking office in 1995, he also served as vice president of Mayors for Peace, an

organization of 1,608 cities around the world that work together to abolish nuclear

weapons and build genuine and lasting peace. Testifying before the International Court of

Justice in 1995, Mayor Itoh argued it was clear that use of nuclear weapons constituted a

violation of international law. He repeatedly lodged protests against all nuclear weapons

tests by nuclear powers.

At the

2005 Review Conference for the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in New York, Mayor Itoh

represented Mayors for Peace by helping to lead a gathering of 40,000 people from around

the world on a march through the streets of the city. He stood up before world leaders at

the United Nations to forcefully present the expectations of the two A-bombed cities that

the nuclear powers will accomplish the total elimination of their nuclear arsenals.

Mayor

Itoh also called for Japan’s continued commitment to its non-nuclear principles in

opposition to suggestions that Japan acquire a nuclear weapons capability following North

Korea’s nuclear test in 2006.

Hiroshima

Mayor Tadatoshi Akiba, in a statement issued as president of Mayors for Peace, said:

“I hereby express my great respect and admiration for Mayor Itoh’s achievements

and offer my heartfelt condolences and prayers for his peaceful repose. I vow to inherit

his passion and, working with the 1,608 members of Mayors for Peace, do everything in my

power to bring about the truly peaceful, nuclear-weapon-free world he so strongly

desired.”

Tomihisa

Taue, 50, the new mayor of Nagasaki, worked as a city government employee for 26 years. He

worked mainly in tourism and public relations. His last job was statistics section chief.

Mr. Taue

is so big-hearted that he is known among his colleagues as “Buddha Taue.” He is

never arrogant, supporters say, but he is candid about his opinions. Mayor Taue wants to

continue to promote his predecessor’s message of peace.

–

edited from The Asahi Shimbun and MayorsforPeace

The Survivors

The Survivors

by Tadatoshi Akiba, Mayor of

Hiroshima

According to Japanese

and Chinese tradition, a sixtieth anniversary begins a new cycle of rhythms in the

interwoven fabric that binds humankind and nature. To understand what the next cycle will

bring, Hiroshima must return to our point of departure and explore the meaning of these 60

years of survival, recovery, and growth.

After I

took office in 1999, I issued a Peace Declaration highlighting the three primary

contributions of the hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors). The first was to transcend

their infernal pain and despair. Hovering between life and death in a corpse-strewn sea of

rubble, they opted to continue living when none could have blamed them for choosing death.

We should never forget the will and courage required for the hibakusha to return to

life as decent human beings.

Their

second accomplishment has been to effectively prevent a third use of nuclear weapons. From

Korea to Vietnam and even Kosovo, strong voices have advocated the use of nuclear weapons.

I truly believe the hibakusha's courage in telling their stories, their eloquent

argument that nuclear weapons are the ultimate evil, and their determination that such

evil never be repeated have helped prevent such madness.

Their

third achievement is the new worldview engraved on the Cenotaph for the A-Bomb Victims

that stands in the middle of Hiroshima's Peace Memorial Park: "Please rest in peace,

for we [the human race] will not repeat the evil." The survivors make this pledge and

totally reject the path of revenge and animosity because they know it leads to extinction.

How did

the hibakusha, just ordinary people like you and me-except they happened to be in

Hiroshima on August 6, 1945-become so determined that "no one else should ever suffer

as we did?" Could it be that a mechanism, perhaps encoded in our genes, is triggered

when a sufficiently large group of people confronts a threat to our collective survival?

Such a mechanism may have shown the hibakusha the truth about nuclear weapons, and

they, in turn, are telling us that we must eliminate these weapons if the human race is to

endure.

People of

faith tend to hear the hibakusha message as a revelation from God. Others react

differently, but most of those who study and understand the hibakusha experience

come to the same conclusion about nuclear weapons. Perhaps this is why more than 1,000

mayors around the world have responded to the Mayors for Peace 2020 Vision Campaign, which

calls for the elimination of all nuclear weapons by the end of the next decade.

The vast

majority of people and nations on Earth want to be rid of nuclear weapons. The hibakusha

have done more than their share to create a safe and peaceful world for the generations to

come. It is now our responsibility to champion the will of the majority and fulfill the hibakusha

vision by ensuring their most cherished desire that no one else ever suffers as they did.

Tadatoshi Akiba is the

president of Mayors for Peace. See: www.pcf.city.hiroshima.jp/mayors/english

– PeaceMeal, July/August2005

My Hiroshima experience

My Hiroshima experience

by Deidre Holmberg

My husband, David, and I visited Hiroshima in the winter of 2002. We took a speed

train, a shinkansen, to the bright lights of what is now a very cosmopolitan,

vibrant place. At first glance, Hiroshima looked like any other Japanese city. People

crowded the sidewalks under the neon signs. The streets were crowded with Toyotas,

mini-vans, and pedestrians. Old men and women headed for home with packages and groceries.

School children, dressed in their navy blue uniforms, walked and laughed together in large

groups.

We visited Hiroshima because we are very interested in

World War II history. We have been fortunate enough to walk the beaches of Normandy, visit

war cemeteries in Italy and Honolulu, and we finally found ourselves able to visit an

historical place of great significance to both Americans and Japanese.

As the granddaughter of a World War II veteran stationed in

the Pacific, I found myself at odds about our nuclear invasion of Japan before I visited.

My grandfather had nearly starved to death on Guadalcanal as he fought seemingly endless

and brutal battles with Japanese forces on the other side of the island. He watched from

the beach as supply ship after supply ship was sunk just a couple of hundred yards from

shore. Suffering from malaria and dengue fever, he would sneak into the Japanese camps and

steal bags of rice from their kitchens. As he was driving in a truck on the island, the

head and shoulders of the truck driver were blown into his lap. He said that knowing that

he was the only person on Guadalcanal that could kill cockatoos with a slingshot, he had

to survive. Who else would feed his men?

My grandfather turned 86 on September 11th and he still

believes that the atomic bombs dropped on Japan saved his life and the lives of many other

Americans. Uneducated as I was before my trip, I believed him.

Our hotel was situated on the banks of Motoyasu River, only

a few hundred feet from the epicenter of the nuclear explosion of 1945. The river is

peaceful now, just like everything else in the center of Hiroshima. Where once was

scorched, hallowed ground, now is a public park lined with statues of remembrance.

Sadako's statue is there, along with hundreds of thousands of paper cranes from all over

the world.

The Peace Museum, home to all artifacts from that fateful

day, is a sacred place. Faces of the lost line the walls. They were not military men. They

were old men and women, children, babies, and young mothers. The atomic bomb wiped out

most of the people and structures within a few thousand yards. They were the lucky ones.

The people unlucky enough to survive the initial explosion were terribly burned, maimed,

deafened, blinded, and poisoned. They crawled, fingerless and shredded, away from the

epicenter only to die in agony days, weeks, months, or years later.

The expression "I wouldn't wish this on my worst

enemy" certainly applies here. I know now that no group of human beings is so bad

that they should be punished with the brutality and inhumanity that nuclear bombs bring.

The people of Hiroshima have moved on, have forgiven as

best they can, and have made a point of working for peace. On display for the world to

view are the scorched school uniforms, buildings, and lunch pails of the unfortunate

Japanese civilians who died at the hands of nuclear energy.

Instead of a way to end the war, the atom bomb attacks of

August 1945 seem to have been a cruel science experiment or maybe a heinous way of showing

the Soviets what we were capable of.

In Hiroshima, I learned that only one U.S. president has

visited the Peace Museum. Not surprisingly, it was Jimmy Carter. Today, as we desperately

seek out "terrorists" that have "dirty bombs," we fail to examine our

own history, our own motives, and our own responsibilities with regard to nuclear power.

Instead of peace, we have again sown war. Today, we use nuclear weapons as a threat to

lord over other nations and we wonder why we are so despised. Even when not in use,

nuclear weapons only bring fear, hatred, and astronomical costs to taxpayers. The making

of these bombs does nothing positive for our environment or for our international image.

May there never be another nuclear attack. May those that

support the propagation of nuclear weapons visit the people and museums of Hiroshima and

Nagasaki. Thank you all for working for my child's future and for the peoples of every

nation.

Deidre Holmberg of Richland teaches biology at Pasco

High School. She brings her peace presence to the sidewalk when she can, at times

accompanied by husband, David, and their infant son, Thomas. Deidre shared her Hiroshima

experience at the Atomic Cities Peace Memorial on August 9th, the anniversary of the

Nagasaki atomic bombing.

– PeaceMeal, Sept/October 2004

Hibakusha doctor visits Hanford

by

Jim Stoffels

Dr. Shuntaro Hida, 84, director of a Tokyo counseling center for

A-bomb sufferers (hibakusha) visited the Hanford community in October to meet with

downwinders and discuss medical treatment. He also shared his personal story of witnessing

the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and treating the victims.

In 1945, Dr. Hida was a young medical officer stationed in the

Hiroshima Military Hospital. Around 2:00 AM on August 6, he was roused from sleep by an

old farmer whose granddaughter was seriously ill. Dr. Hida rode on the back of the

farmer's bicycle to the village of Hesaka six kilometers away to treat the girl, and

stayed overnight. He awoke at ten past eight and, as he prepared to give the girl an

injection, saw a silvery B-29 flying at high altitude toward Hiroshima.

Suddenly he saw a bright flash and felt heat on his face and arms.

He heard no sound but, looking toward the city, saw a white cloud growing from a ring of

fire in the sky. Underneath, a black cloud of dirt and debris kicked up by the blast

spread out and raced toward him. Seconds later, the blast blew him through two rooms of

the farmer's house into a wall and collapsed the roof on top of him.

Dr. Hida escaped from the rubble and began to bicycle back to the

hospital in Hiroshima. On the way he encountered a strange figure, human only in shape — all black, bloody and covered with mud. The body and face were

burnt and swollen. What seemed to be shreds of clothing hung from the body, but on closer

approach was seen to be skin. The "man" fell at Dr. Hida's feet and died. It was

the first A-bomb victim he saw.

More people in the same condition became walking out of Hiroshima,

so many Dr. Hida could not ride is bicycle through them. So he got into the river which

borders the city in order to make his away. He talked to people, asked if they were

alright, but they didn't respond — just stared and walked straight

ahead. Dead bodies of women and children floating in the river bumped into them, so many

he became distraught. Besides, a firestorm was raging in the city. So he turned back to

the village to help set up an emergency field hospital.

In Hesaka, the streets were already so full of bodies, other

people fleeing had to walk on them. When he remembers these events even now, Dr. Hida

said, he feels shame because he could do nothing for the horribly injured victims. He had

no medicine or instruments, and he could not look into the eyes of those he knew were

going to die.

A young mother with a burnt face entreated Dr. Hida to treat the

baby she carried on her back before the others. The woman was insanely desperate. Her

other three children burned to death when their house erupted in flames. The baby was

already dead, but Dr. Hida bandaged it and told the mother to let him sleep. She was so

happy. Three days later, she died vomiting blood.

Many others exhibited the same symptoms. They developed an intense

fever, began bleeding from the mucous membranes and losing their hair. Within hours they

died. It was radiation sickness — the atomic bomb disease, but no one

knew it at the time.

Thirty thousand victims died in Hesaka alone. By the end of 1945,

140,000 died in Hiroshima and 70,000 more in Nagasaki.

During the American occupation, Japanese people were forbidden to

talk or ask about what happened. If they did so, they were arrested. The United States

didn't want the Soviet Union to get any information about the atomic bomb or its effects.

Dr. Hida was arrested four times. The freedom to talk about their experience didn't come

until ten years after the bombing.

A-bomb sufferers began to gather around Dr. Hida, and he became

their advocate. He was the first one to urge the hibakusha to seek medical treatment and

compensation from the American government. For doing so, he was labeled an extreme

leftist.

"I am a doctor," Dr. Hida said. "That's why I

respect human life. It's more important than power or money."

- PeaceMeal, Nov/December 2002

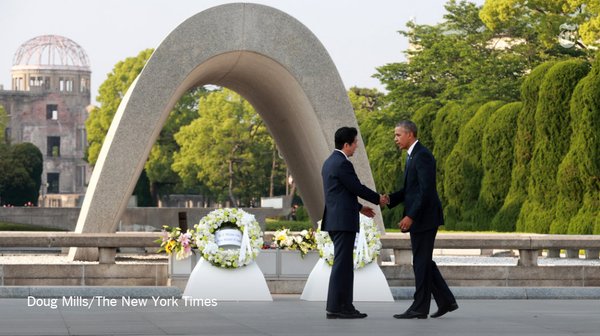

Photo caption: President Barack Obama and

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe shake hands after placing wreaths at the Hiroshima

Peace Memorial in memory of those who died from the atomic bombing. The iconic

“atomic dome,” the only building left standing near the hypocenter of the

A-bomb’s blast, is in the background.

Photo caption: President Barack Obama and

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe shake hands after placing wreaths at the Hiroshima

Peace Memorial in memory of those who died from the atomic bombing. The iconic

“atomic dome,” the only building left standing near the hypocenter of the

A-bomb’s blast, is in the background.

My Hiroshima experience

My Hiroshima experience